The Great Hall of the Jefferson Building, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. Photo by Dan Vera.

A position held by 49 of the nation’s most heralded poets, the Poetry Consultant/Poet Laureate at the Library of Congress provides a perspective unique in American letters on the evolving literary landscape and the way American society has been challenged and changed over the past 80 years.

Joseph Auslander convinced Archer Huntington to fund a position dedicated to poetry at the Library of Congress in 1937. Later Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish made significant modifications that in effect created the position we know now, which has evolved from a largely reference position as “Chair of Poetry” in the Library’s Books & Manuscripts division to its ever-expanding role as public relations focal point for poetry in the United States.

Studying the position’s history reveals clear evidence of and exceptions to America’s narrow cultural mores. Consider that after the wartime appointments of three women in the 1940s (Louise Bogan, Léonie Adams, and Elizabeth Bishop), a full two decades would pass before another woman was appointed to the position in 1971 (Josephine Jacobsen). And though the subsequent record has improved somewhat, it remains abysmal that only twelve of the 49 poets who have held the position have been women.

The record on racial and ethnic diversity is even worse: it took three decades before the first non-white poet, Robert Hayden, was appointed. And of the 49 poets to be appointed, only six have been people of color. Promisingly, the most recent period has been the most diverse in the position’s history, with more expansive choices, including the first openly LGBT poet to hold the position, Kay Ryan (William Meredith was not out at the time of his appointment) and the first Latino poet to hold the position, Juan Felipe Herrera, to hold the position (William Carlos Williams was prevented from serving due to McCarthy-era hysteria).

What to make of the fact that later consultants Hayden and Gwendolyn Brooks, although prolific and active during the period, are wholly missing in any correspondence or archives of the Poetry Office prior to 1962? These absences are representative of the Library’s limited view of American poetry during the 1940s and 50s. Things began to open up in the 1960s, first during the laureateship of the poet and anthologist Louis Untermeyer, whose great accomplishment in the position was the National Poetry Festival, which featured Langston Hughes and Gwendolyn Brooks.

After World War II, a long line of veterans served in the position until 1970 when, at the height of the Vietnam War, William Stafford was appointed. Stafford was a remarkable choice, not only for having been a conscientious objector during World War II, but also for being the first West Coast poet to hold the position – there have only been seven.

There is so much more to be discovered in the largely unknown history of this position. After having enjoyed the opportunity to guest edit the first Poets Laureate issue in 2009, I am delighted in Beltway Poetry Quarterly‘s valedictory twentieth year to have the opportunity to revisit the “catbird’s seat,” as Conrad Aiken called it, with this expanded issue. The sterling contributions of that earlier issue have been entwined with new excerpts, photographs, and vignettes, along with poetry by, interviews with, and new essays on Gwendolyn Brooks, James Dickey, Juan Felipe Herrera, Philip Levine, W.S. Merwin, Howard Nemerov, and Karl Shapiro. I’m delighted as well to honor the indispensible work of the Poetry Office at the Library of Congress by including a section highlighting the tireless work that has made the laureateship possible over the years. I’m indebted to the authors of these new essays, and want to especially thank Grace Cavalieri, who has allowed us to incorporate excerpts from her interviews with recent laureates in this issue. In addition, I would like to especially highlight Peter Montgomery‘s careful eye and judicious grammatical counsel in copyediting this issue.

My hope has been to present a festschrift of sorts to the Poet Laureateship at the Library of Congress, one that not only expands our understanding of the evolution of this position over time, but also highlights its singular position and promise in American letters.

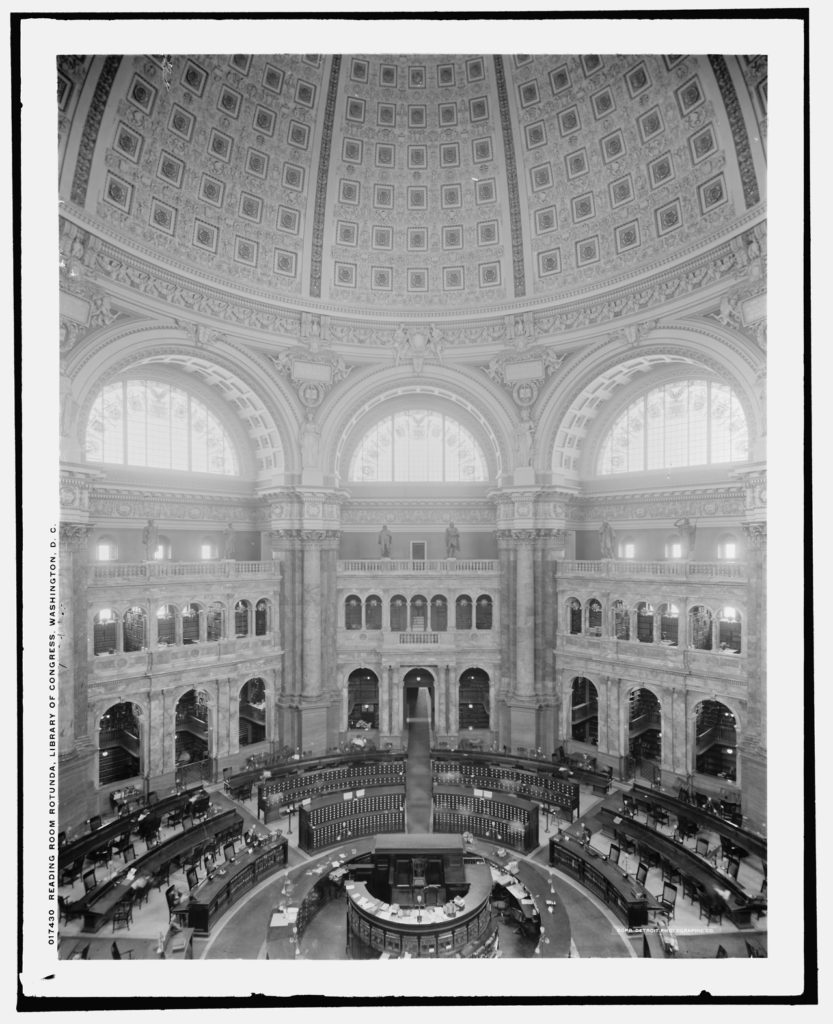

Main Reading Room, Jefferson Building, 1904. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Dan Vera is the co-editor of the anthology Imaniman: Poets Writing in the Anzaldúan Borderlands (Aunt Lute Books, 2016), and author of two poetry collections: Speaking Wiri Wiri (Red Hen Press, 2013), and The Space Between Our Danger and Delight (Beothuk Books, 2008). Vera’s work is featured online at the Poetry Foundation website and in college and university curricula, various journals, and anthologies including Ghost Fishing: An Eco-Justice Anthology, the bilingual Al pie de la Casa Blanca/Knocking on the Door of The White House: Latino and Latina Poets in Washington, D.C., Queer South, Divining Divas, and Full Moon On K Street: Poems About Washington, DC. A CantoMundo and Macondo writing fellow, he’s a recipient of the Oscar Wilde Award for Poetry and the Letras Latinas/Red Hen Poetry Prize, as well as grants and fellowships from the DC Commission of the Arts & Humanities, the Humanities Council of Washington, DC, the Ragdale Foundation, and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. His other projects include the small literary presses Poetry Mutual and Souvenir Spoon Books, and co-curating the literary history website, DC Writers' Homes. Born and raised in South Texas, he lives in Washington, DC. For more visit http://www.danvera.com. To read more by Dan Vera: Dan Vera: Winter 2006; Dan Vera: Evolving City Issue; Dan Vera: Split This Rock Issue; Dan Vera's Introduction to the US Poets Laureate Issue,Fall 2009; Dan Vera: Langston Hughes Tribute Issue; Dan Vera: Floricanto Issue.