My first encounter with Charles Simic‘s work wasn’t an introduction to the person. Prior to that encounter, his name seemed to be something that breathed and moved on its own—popping up in conversations with other writers, and making its appearances in various journals. It is also emblazoned on the spines of numerous collections of poems.

His first poems were published in 1959, when he was 21. His first full-length collection of poems, What the Grass Says, was published the following year. Since then he has published more than sixty books in the U.S. and abroad, twenty titles of his own poetry among them. His poetry collections include That Little Something (2008), My Noiseless Entourage (2005), and Selected Poems: 1963-2003 (2004), among others.

Simic is a recipient of several honors that include the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1990, a finalist for the National Book Award in 1996, a Griffin Prize in 2005, and he was the 15th U.S. Poet Laureate (2007-2008).

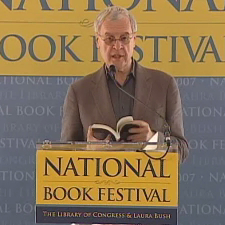

Photo: Library of Congress

I would later learn that Simic was born on May 9, 1938, in Belgrade, Yugoslavia. The 71-year-old is also an essayist, translator, editor and professor emeritus of creative writing and literature at the University of New Hampshire, where he has taught for 34 years.

One might think, with Simic being such a prominent literary figure, that I should have come to his work much sooner than 2009. But the late Nobel Prize winner Albert Szent-Gyoryi defined discovery as an accident meeting a prepared mind. At the time of my accidental meeting with Simic’s work, I was browsing online journals, looking for places to submit my work when I came across Simic’s poem, “Doubles,” and was hooked.

Simic’s “deliberately simple structure and diction in his poems” as a way of presenting difficult subject matter is widely praised by critics. Among them was Librarian of Congress James Billington who described Simic’s work as a collection of “stunning and unusual imagery”: “He handles language with the skill of a master craftsman, yet his poems are easily accessible, often meditative and surprising.”

In “Doubles,” the idea of humans “inhabited by an inner family of selves,” or having multiple personalities, is made accessible through his use of plain language. Through most of the poem, it’s clear that the speaker and the doubles are separate individuals. What Billington cited as the “flashes of ironic humor” in Simic’s work starts with the fifth line of the second stanza to the end, when the doubles become the speaker’s “many selves”:

The last time anyone saw me alive;

I was either wearing dark glasses

And reading the Bible on the subway,

Or crossing the street and laughing to myself.

Another example of Simic’s “ironic humor” is in his poem, “Eyes Fastened With Pins.” Defying easy categorization, some of his poems offer a surreal and metaphysical reflection while others offer grimly realistic portraits of violence and despair. Vernon Young, a Hudson Review contributor, noted that the common source of Simic’s poetry was memory:

Simic, a graduate of NYU, married and a father in pragmatic America, turns, when he composes poems, to his unconscious and to earlier pools of memory. Within microcosmic verses which may be impish, sardonic, quasirealistic or utterly outrageous, he succinctly implies an historical montage. His Yugoslavia is a peninsula of the mind…. He speaks by the fable; his method is to transpose historical actuality into a surreal key…. [Simic] feels the European yesterday on his pulses.

Simic once said, “Poetry is an orphan of silence. The words never quite equal the experience behind them.” Those experiences include his formative years spent in Belgrade. His family evacuated their home several times to escape indiscriminate bombing. The atmosphere of violence and desperation continued after the war. Simic’s father left the country for work in Italy, and his mother tried several times to follow, only to be turned back by authorities.

In a 1998 interview, Simic told the Cortland Review how those experiences affected his writing:

“Being one of the millions of displaced persons made an impression on me. In addition to my own little story of bad luck, I heard plenty of others. I’m still amazed by all the vileness and stupidity I witnessed in my life.”

When he turned 15, Simic’s mother arranged for the family to travel to Paris. He spent a year there studying English in night school and attending French public schools during the day. Simic, along with his mother and brother, sailed for America and reunited with his father in the Oak Park suburb of Chicago, where he enrolled in high school. They lived there until 1958. Three years after, he was drafted into the U.S. Army, and in 1966 he earned his Bachelor’s degree from New York University while working at night to cover the costs of tuition.

While Simic feels “the words never quite equal the experience behind them,” Tim Green, editor of Rattle, noted that poetry not only allows the reader to step into the poet’s shoes but also the poet’s body, mind, and moment in time. Green went as far as to define the craft as “an art of ventriloquism.” In that case, Simic and his readers work “symbiotically to create an acoustic and linguistic experience” every time his poems are read.

Eric Williams, an Artful Dodge contributor, observed the narrative thread that binds the images together in Simic’s work. He noted that the readers are hit with “a dazzling series of loosely connected images.” Often times the final line of Simic’s poems connect everything.

The Antioch Review‘s Diana Engelmann noted the “dual voice” of Simic’s poetry that speaks both as an American and as an exile:

While it is true that the experiences of Charles Simic, the ‘American poet,’ provide a uniquely cohesive force in his verse, it is also true that the voices of the foreign and of the mother tongue memory still echo in many poems. Simic’s poems convey the characteristic duality of exile: they are at once authentic statements of the contemporary American sensibility and vessels of internal translation, offering a passage to what is silent and foreign.

Simic discussed his creative process in an interview on Artful Dodge:

When you start putting words on the page, an associative process takes over. And, all of a sudden, there are surprises. All of a sudden you say to yourself, ‘My God, how did this come into your head? Why is this on the page?’ I just simply go where it takes me.

Charles Simic Selected Bibliography

What the Grass Says, 1967

Somewhere Among Us a Stone is Taking Notes, 1969

Dismantling the Silence, 1971

White, 1972

Return to a Place Lit by a Glass of Milk, 1974

Charon’s Cosmology, 1977

School for Dark Thoughts, 1978

Classic Ballroom Dances, 1980

Austerities, 1982

Weather Forecast for Utopia & Vicinity: Poems 1967-1982, 1983

Unending Blues, 1986

The World Doesn’t End: Prose Poems, 1989

The Book of Gods and Devils, 1990

Hotel Insomnia, 1992

Dime-Store Alchemy, The Art of Joseph Cornell, 1993

A Wedding in Hell, 1994

Walking the Black Cat, 1996

Jackstraws, 1999

Night Picnic, 2001

A Fly in the Soup: Memoirs, 2002

The Voice at 3:00 A.M.: Selected Late and New Poems, 2003

Selected Poems, 1963-2003, 2004

My Noiseless Entourage, 2005

Aunt Lettuce, I want to Peek Under Your Skirt, 2005

Monkey Around, 2006

Sixty Poems, 2008

That Little Something, 2008

Monster Loves His Labyrinth, 2008

Master of Disguises, 2010

New and Selected Poems: 1962-2012, 2013

Selected Early Poems, 2013

The Lunatic, 2015

The Life of Images: Selected Prose, 2015

Scribbled in the Dark, 2017

Originally published in Volume 10:4, Fall 2009.

Alan King is the author of two books of poems: Point Blank (Silver Birch Press, 2016) and Drift (Willow Books, 2012). A Caribbean American, whose parents emigrated from Trinidad and Tobago to the US in the 1970s, he is a husband, father, and communications professional. He is a Cave Canem graduate fellow, and holds a Masters of Fine Arts in Creative Writing from the Stonecoast Program at the University of Southern Maine. King has been nominated multiple times for Pushcart Prizes and Best of the Net selections. He lives with his family in Bowie, MD and blogs about art and social issues at alanwking.com. To read more by this author: Alan King: Museum Issue; Alan King on Karibu Books: Literary Organizations Issue.