Volume 15:4, Fall 2014

A Splendid Wake Issue

[P]oets are some of feminism’s most influential activists, theorists, and spokeswomen; at the same time, poetry has become a favorite means of self-expression, consciousness-raising, and communication among large numbers of women not publicly known as poets.

Jan Clausen, A Movement of Poets

Many people are enamored with Washingtons corridors of power. They want to walk among elected officialsSenators, Representatives, the minions that serve themor rub elbows with the national policy makerselected, appointed, or bureaucraticwho shape laws and regulations. Or they want to connect with private power brokers: lobbyists, lawyers, and corporate representatives. Yes, these people want to change the world through proximity to legislative power, but this interest in power, these connections to Washington, DC never resonated for me.

The Washington, DC that captures my imagination was the city where lesbian poets and movement activists lived. The city where lesbians walked, organized, wrote, collaborated, labored, and loved is the Washington I want to record and recuperate. From the late 1960s through the late 1980s, a movement of lesbian poets flourished. While bureaucrats and politicians languished in closets using money and power to attack women and undermine their rights as citizens, some lesbians lived openly, writing and celebrating their lives within communities of affection and affinity. They shared their work through national networks of lesbians and feminists. These poets, these cultural activists, imagined a world where lesbians lived with full equality; they imagined a world transformed by feminism; they imagined new types of bodies, new forms of body politics. They used old words and gave them new meanings; they created new words invigorating language; they viewed poetry as a site of transformative activism. Ordinary streets of Washington inspired these women. These are six stories from Washington, DC about lesbian poetry.

1.

Cheryl Clarkes first full-length poetry collection, Living as a Lesbian, opens on 14th Street in 1968. The street was gutted. Clarke writes:

Fire was started on one side of the street.

Flames licked a trail of gasoline to the other side.

For several blocks a gauntlet of flames.

For several days debris smoldered with the stench

of buildings we had known all our lives. Had known

all our lives.

From this day her sense of place was cauterized. Cauterize: to burn with a hot iron, especially for curative purposes. A perfect word to capture the experience of seeing a race rebellion. For Clarke, the city where she was raised, her familys ancestral home had become a buffalo and nearly a dinosaur. Endangered. On its way to extinction because, as Clarke concludes the poem, that is what happens with everything else white men have wanted for themselves.

From this day her sense of place was cauterized. Cauterize: to burn with a hot iron, especially for curative purposes. A perfect word to capture the experience of seeing a race rebellion. For Clarke, the city where she was raised, her familys ancestral home had become a buffalo and nearly a dinosaur. Endangered. On its way to extinction because, as Clarke concludes the poem, that is what happens with everything else white men have wanted for themselves.

From her earliest chapbook, Narratives, through her collected poetry and prose, The Days of Good Looks, Clarke grapples with preservationpreserving the spirit of resistance and rebellion among African-Americans, women, lesbians, queers. Inspired by rebellions on the streets of Washington, Clarke ignited rebellions through her work over the next forty-five years.

2.

On Thursday, 1 October 1981, over at 624 9th Street NW near G Street, a hospitality suite at the YWCA greeted attendees of the second Women in Print conference. Organized by two DC feminist institutions, the womens bookstore Lammas and the newspaper off our backs, the second Women in Print conference convened 120 women print activists in Washington. Although only five years after the first Women in Print conference in Nebraska, a number of new feminist publications, publishers, and bookstores attended the gathering. The movement was growing. Print activists participated in an array of workshops, panels, and discussions held at the 4-H Center. Featured workshops for bookstores included topics like inventory, staffing, and time management, workshops for periodicals on structures, finances, fundamentals of layout and design, and the politics of reviewing; workshops for publishers that tackled issues like trouble-shooting pressroom problems and Feminism and Capitalism: How can we work within conflicting structures. General sessions grappled with how to create A Lesbian Literature (with particular attention to race, class, age, and disability) and issues confronting third world women writers and editors. The four-day conference was a dynamic gathering of movers and shakers in all aspects of feminist print culture. From the conference, women drew inspiration for new work, made connections for new collaborations, and initiated new erotic and intimate partnerships.

3.

Before she moved to Washington, DC, Rita Mae Brown imagined The Presidents Bedchamber. While the Vietnam War raged, Brown conjured the President lying in bed at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. She imagined him, almost vulnerable with a wry assessment of his own limitations:

Before she moved to Washington, DC, Rita Mae Brown imagined The Presidents Bedchamber. While the Vietnam War raged, Brown conjured the President lying in bed at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. She imagined him, almost vulnerable with a wry assessment of his own limitations:

He lies awake at night

With his hand over his heart

Because he is not sure

If its still there.

Browns critique of politicians, which many may still find resonant today, is coupled with her vision for radical social change through language and culture. In December 17, 1971 to December 17, 1972 A Narrative, Of Sorts, Brown writes,

Language is the roadmap of a culture

And this is when the language leaves me

As wind before water

This is no longer a poem

This is an effort to find a form for the unspeakable.

Brown, like many feminist poets, struggled with the need to use languageand all of its patriarchal trappingsas generative for revolution. Speaking the unspeakable includes these commands:

Wake up, sisters!

Wake up, my beautiful, my handsome woman

Our country is lost

Our citizens are dying

The world is unravelling

And the sun hides the stars in a lie of light.

Brown continues describing the enemies (often configured in polemical rhetoric as patriarchy, racism, and imperialism, though here rendered more poetically) as those who walk this earth/Who would destroy us all. Brown recognizes, however, both the internal and external nature of oppression. She concludes the poem:

Wake up, people

To this, the cruelest thought:

As the beast stalks the land

So the beast lies within

Each of us

Even her breast

Even mine

And these tears making a mockery of my courage

Are for my pain

Are for the beast within us and the saint as well

And for her

Because a butterfly is folding its wings.

Brown seeks to incite women to revolution through these poems from the early 1970s. While she did not spend lot in the Washington, DC area, Browns fingerprints on lesbian-feminist activism are legionshe wrote poems, was an influential member of The Furies, helped Diana Press start their publishing activities, and worked on the anthology Dykes For An Amerikan Revolution, published by Easter Day Press in Washington, DC. With Rita Mae around, the revolution seemed close at hand.

4.

At some point in 1973, Judy Grahn read in Washington, DC. Grahn was not yet the legendary poet, literary critic, and feminist/queer theorist that she would become. She was a young woman, an instigator of the Oakland, CA-based Womens Press Collective, the author of Edward the Dyke and Other Poems, the Elephant Poem Coloring Book, and the newly released The Common Woman. In Washington, Grahn met women from the Furies Collective; after the Furies dissolved, collective members spawned other radical lesbian projects. Meg Christian and Ginny Berson discussed one of these projects with Grahn while she was in DC; they said that they were starting a record company. Grahn describes an evening where Ginny leaned forward and said emphatically, we want your poetry to be our second album. Grahn remembers being flattered and agreeing, but just barely hiding her skepticism. Lots of people had big ideas. Making them come true was the tricky part. Christian and Berson were not all talk, however. They started Olivia Records, and their fourth album was a spoken word album titled, Where Would I Be Without You with poetry by Grahn and Parker. Olivia became one of the most successful and enduring independent record labels of all time.

5.

Over at Maryland and 10th Street NE is Minnie Bruce Pratt. She is looking at shattered glass in the street. She sees, smashed sand glittering on a beach of black asphalt or as bits of broken kaleidoscope,/or as crystals spilled from the white throat of a geode. Pratt uses metaphor to move the glass as far as possible / from the raised hands that threw the bottle. Connecting the sharp glass with how we use words, Pratt concludes with this couplet: You can work to the surface the irritant, pain, the glass/sliver to blink in the light, sharp as a question.”

Over at Maryland and 10th Street NE is Minnie Bruce Pratt. She is looking at shattered glass in the street. She sees, smashed sand glittering on a beach of black asphalt or as bits of broken kaleidoscope,/or as crystals spilled from the white throat of a geode. Pratt uses metaphor to move the glass as far as possible / from the raised hands that threw the bottle. Connecting the sharp glass with how we use words, Pratt concludes with this couplet: You can work to the surface the irritant, pain, the glass/sliver to blink in the light, sharp as a question.”

In Sharp Glass, urban detritus gives Pratt an opportunity to think about injustice and inequality in our nations capital. In By the Corner at F Street, Pratt continues these meditations, writing the unseasonable wind jostles / branches on the haw tree, unleaded almost bare in the sun. She sees someones cold hand and arm and unhooked body, then she speaks with T.C. who wouldnt say where he slept / but he was pleased to shake hands after our conversation. This poem is an intimate portrait of contrasts: Pratts intimacy with her lover, the heat in her apartment from the radiator sizzles like a hot skillet which is paid for with the rent, the way she waits inside, drinking hot tea behind my thick door contrasts with an external world where people are homeless and must spend nights in shelters. In another example, Pratt describes her work at the polling place asking for votes for the woman / who believes in bottle deposits: so people on the street / can pick up a little money. Pratt understands the power in Washington, and she highlights how it can be blind to human needs. The poem ends, In the streetlight dark, I can scarcely see your eyes, // as you shout some encouragement over the bitter wind. Pratts poems often make visible things that are obscured and offer some encouragement even as they highlight bitterness and injustice.

6.

E. Sharon (Lois) Gomillions Forty Acres and a Mule, illustrated by Casey Czarnik, one of the owners and operators of Diana Press in Baltimore, MD, is a small chapbook, printed by Diana Press. It begins with the calculation: 40 acres + 1 Mule x 400 years = bitterness.” The poems of Forty Acres and a Mule offer important critiques of a variety of subjects from the perspective of an African-American feminist. In the first poem Wake Up! Brothers And Sisters, Gomillion implores her Brothers and Sisters to Stand Up! And Wake Up! telling them, Dont you see what the Man is doing/Just another one of his plots brewing.

In 1973, Gomillion recognized the effects of gentrification on Washington, DC. In a poem titled, Soul Food Goes Elite, she begins, Hamhocks and collard greens/On white folks tables you aint never seen and concludes that curiosity and publicity bring Even the rich to slip and try,/Potato salad, porkchops, even tatoe pie. Forty years later, Gomillions commentary about life in Washington remain sharp and apt.

Gomillion also observes class dynamics within the African American community. In the poem Dem Black Executives, Gomillion notes that the voices of the executives have changed, No more dems and doos / now its them and those. She wryly comments, Youve even changed your dating mate / no sister for you / Only a blond will do. From these lines, Gomillions command of compression, rhythm, and rhyme are evident as well as her sly, cutting sense of humor.

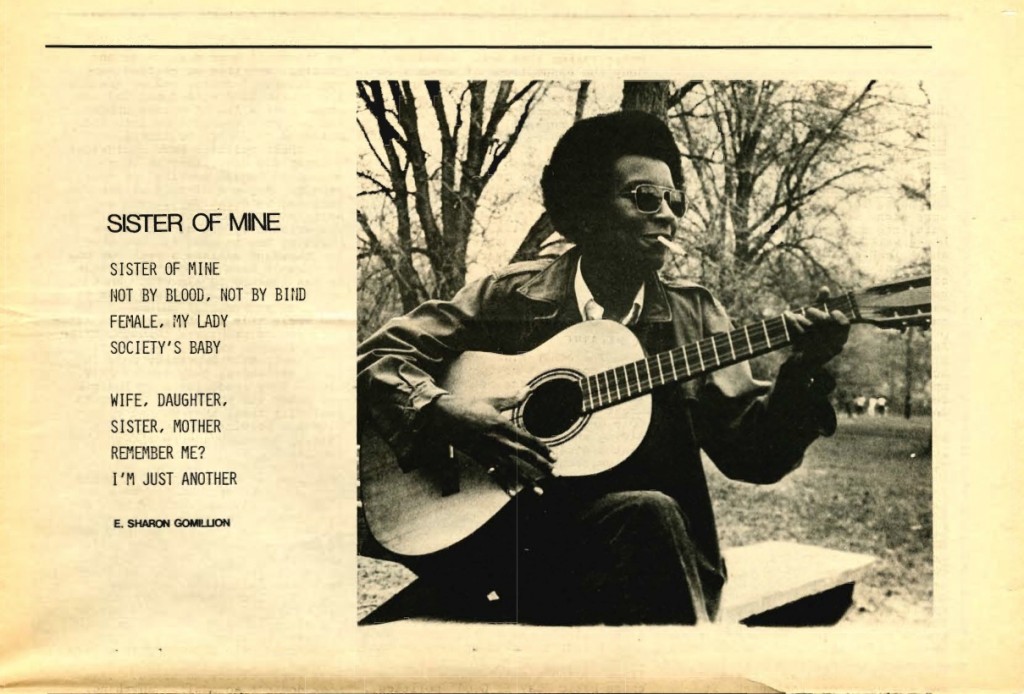

The February 1973 issue of The Furies contains a poem by Gomillion not included in the collection Forty Acres and a Mule. Sister of Mine capture some of the feelings about feminism and sisterhood in the US during the early 1970s. Here is Sister of Mine in its entirety:

Sister of Mine

Not by blood, not by bind

Female, my lady

Societys babyWife, daughter,

Sister, Mother

Remember Me?

Im just another.

In these two quatrains, Gomillion expresses the zeal and possibility of womens relationships with one another. Not by blood and not by bind, lesbian-feminist poets imagined new moments of glory and scribbled them into being.

Sources

Rita Mae Brown, The Hand that Cradles the Rock, Diana Press, 1971

Cheryl Clarke, Living as a Lesbian, Sinister Wisdom/A Midsummer Nights Press, 2014

E. Sharon Gomillion, Forty Acres and a Mule, Diana Press, 1973

E. Sharon Gomillion, Sister of Mine, The Furies, January/February 1973

Judy Grahn, A Simple Revolution, Aunt Lute, 2012

Minnie Bruce Pratt, We Say We Love Each Other, Spinsters/Aunt Lute, 1985

Julie R. Enszer is the author of Lilith's Demons (A Midsummer Night's Press, 2015), Sisterhood (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2013) and Handmade Love (A Midsummer Night's Press, 2010). She is editor of Milk & Honey: A Celebration of Jewish Lesbian Poetry (A Midsummer Night's Press, 2011), a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award in Lesbian Poetry. She has her MFA and PhD from the University of Maryland. Enszer is the editor of Sinister Wisdom, a multicultural lesbian literary and art journal, and a regular book reviewer for the Lambda Book Report and Calyx. Her website: www.JulieREnszer.com. To read more by this author: Julie R. Enszer on The Furies; Four poems, Spring 2011