Volume 15:4, Fall 2014

A Splendid Wake Issue

Born in Alliance, Nebraska in 1921, James Andrew Emanuel found early jobs on farms and ranches, including vacation work as what he calls a summertime cowboy, herding cattle on the ranch of Charlotte Worley, reputedly a pistol-toting, fearless woman. He left home at the age of 17 to explore the world and he never turned back.

He held a series of odd jobs and professional assignments, ranging from elevator operator and junkyard worker to professional basketball player (the Five Aces played several games in only one Midwestern tournament, seemingly the first African-American professionals) and Confidential Secretary to Brigadier General Benjamin O. Davis, Sr. Emanuel earned degrees at Howard and Northwestern Universities and at Columbia, where he received his Ph.D.

In the 1960s he taught at City College of the City University of New York, where he was instrumental in getting the work of African-American writers onto undergraduate reading lists. In the 1970s he went to Europe on a Fulbright and taught at the Universities of Toulouse, Grenoble, and Warsaw. From 1986 on, he lived in Paris in a sixth-floor walk-up in Montparnasse, though occasionally traveling to take part in conferences, and in collaborative artistic endeavors. In the early 90s, Emanuel invented a new poetic form which he named “Jazz-and-Blues Haiku.” “I use it as a jazz basis to say all that Black Americans would say about African American life. It was a form that chose me. On occasion others incorporate the accompaniment of a jazz saxophonist into the performance of the haiku.”

In the 1960s he taught at City College of the City University of New York, where he was instrumental in getting the work of African-American writers onto undergraduate reading lists. In the 1970s he went to Europe on a Fulbright and taught at the Universities of Toulouse, Grenoble, and Warsaw. From 1986 on, he lived in Paris in a sixth-floor walk-up in Montparnasse, though occasionally traveling to take part in conferences, and in collaborative artistic endeavors. In the early 90s, Emanuel invented a new poetic form which he named “Jazz-and-Blues Haiku.” “I use it as a jazz basis to say all that Black Americans would say about African American life. It was a form that chose me. On occasion others incorporate the accompaniment of a jazz saxophonist into the performance of the haiku.”

Emanuel is author of a critical study of Langston Hughes; editor with Theodore Gross of one of the first anthologies of African-American literature (Dark Symphony, Free Press, 1968); author of 13 books of poetry, and an autobiography combined with sections of poetry, poetic drafts, photos, and bibliographic and travel notes (The Force and The Reckoning, Lotus Press, 2001). Emanuel has been honored with numerous awards, and has many admirers within the poetry world; but he is not very well known generally by the American public.

Emanuel is author of a critical study of Langston Hughes; editor with Theodore Gross of one of the first anthologies of African-American literature (Dark Symphony, Free Press, 1968); author of 13 books of poetry, and an autobiography combined with sections of poetry, poetic drafts, photos, and bibliographic and travel notes (The Force and The Reckoning, Lotus Press, 2001). Emanuel has been honored with numerous awards, and has many admirers within the poetry world; but he is not very well known generally by the American public.

From the Summer of 2000 to the summer of 2013, my CUNY students and I were lucky enough to have James Emanuel visit my “Paris through the Eyes of Travelers” class as a guest artist, reading his poetry, and sharing his wisdom about poetry and life. His presentations were always inspiring, a highlight of the course.

From the Summer of 2000 to the summer of 2013, my CUNY students and I were lucky enough to have James Emanuel visit my “Paris through the Eyes of Travelers” class as a guest artist, reading his poetry, and sharing his wisdom about poetry and life. His presentations were always inspiring, a highlight of the course.

James Andrew Emanuel passed away in 2013 and is buried in Pere Lachaise Cemetery, the same resting place as Richard Wright.

What follows are James Emanuels unedited answers to my questions, posed to him in 2009, and first published (in a slightly different version) on my blog, “Writing from the Heart, Reading for the Road.” It is my hope that sharing this with a new audience will help bring overdue attention to the work of someone who I (and many others) believe is one of Americas greatest contemporary poets. I know that reading his poetry will enrich the minds, hearts, and lives of all who are open to what it has to give.

What would you like people to know about your life and your work?

He who steals my purse steals trash,

but he who robs me of my good name

steals that which cannot enrich him,

but which will leave me poor indeed.

from Shakespeares Othello

Like a fighter first tensing his arm to deflect a suspected low blow, I begin answering these questions about my life and my poems by declaring that an 18-line poem entitled Hows Life? occupied half an Internet page published bypoetry.com, self-styled “The International Library of Poetry,” with a street address in Owings Mill, MD. Closely beneath the poem is the authors name, James Emanuel, followed immediately by Copyright © 2003 James Andrew Emanuel. The first half of the text follows:

Hows life you ask?

Life is long,

life is friendless,

life is full,

life is sad,

life has just begun,

life is bitter,

life is content,

life is predestined.

This poem is almost meritless. As one of the three authors of the book How I Write/2 (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972), I wrote the 77-page section Poetry Writingand so could fairly comment on Hows Life? as poetry. However, I limit my offering to this statement: I, legally both James Emanuel and James Andrew Emanuel, never saw the above-mentioned poem or heard of its existence before January 3, 2003, when an acquaintance faxed me a copy of it with a note, Found on the web just now. Its internet publisher, poetry.com, during correspondence initiated by me, refused to provide information of any kind, including means to contact the customer who putatively shares my full name. Either the god of Chance or the shame of cowardly villainy is at work. Perhaps something in Daniel Schneiders Internet essay The Not So Strange Emanuel Case (written, I believe, in 2001) speculates the developments in this situation. [Note: A search for the poem in August 2009 turned up empty, leading to speculation that it may have been removed from the Internet on threat of legal action.]

I wish that as many people as possible would read my works, especially my best poems; and I wish that competent, honest critics among those readers would try to make my literary reputation just and ample, as I think I expressed it in my soon-to-be-published essay on the late French critic Michel Fabre.

Readers interested in my many years as a human, as some mid-century poets from the Caribbean (Bob Marley, for example) sang that condition, can find my autobiography in The Force and the Reckoning (Detroit: Lotus Press, 2001).

Why is poetry important? And what is most important about it?

Why is poetry important? And what is most important about it?

Poetry is important because reading it, and certainly writing it, brings the whole man and woman into activity, just as stretching and reaching are vital exercises in formally planned training. A person reading a new poem expects to encounter unusual combinations of familiar words; thus he has agreed to accept changes, however smalland hence however vastin his being. Juggling the common sign at a railroad crossing, we could say that one change can hide another. Jumping minor steps in similar processes, we might claim that reading or writing poetry could lead to revolutionary thought. Dictators keep their eyes on libraries, and in our truly thoughtful moments we know why.

You have worked collaboratively with artists in other mediamusicians and visual artistsand you have expressed the hope that in the future, more artists will work collaboratively across disciplines. Why do you think this is important?

My belief that future poets, artists, musicians and like-minded people should collaborate is important because mankind will not earn the right to survival on earth unless in groups (lone efforts will not suffice, so vast and constant the task will be) we teach one another that what we as individuals have learned are survival needs. These needs are hardcore, insistent, as pleasant as beauty, as simple as courtesy. Society will have begun to do its hard job well when a tired, dirt-poor farmer and a relaxing cutie-pie artist would both feel the same small glow of satisfaction upon seeing a perfectly shaped, well-washed potato.

I was intrigued by the title you came up with the other day when one of my students asked you what your favorite book was (The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin). What is it that you love about that book?

I admired The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin for more than one reason. It reminded me that all men must live through problems. My favorite image from the book is young Benjamin (later to become a famous man, I told myself while reading it) walking down the streets of Philadelphia with his pockets bulging from rolls of bread crammed there, his cheeks similarly distended by the constraints of near-poverty. As an adult he helped draft the Constitution, wrote Poor Richards Almanac (a 25-year production that I partly examined as a boy), and, while walking the ambassadors circuit in Paris, kept his eye on young ladies. I did not appreciate Franklins last-mentioned tendency, for while reading and working as a boy, I placed no value on girls. However, awaiting my Civil Service assignment at the age of 19 in Washington, DC, rereading the autobiography while other newcomers were complaining that they had nothing to do, I began the practice that I had found without merit in Franklin the diplomat.

With a little bit more time to think about it, what are some of your other favorite books?

A little bit more time seems seldom to have been granted me, even to remember other favorite books. Herman Melvilles Moby Dick, however, does rather quickly come to mind, especially the main whaling scenes, Ahab and Starbucks discussions, and the chapter The Whiteness of the Whale. Ralph Ellisons The Invisible Man engrossed me because of his understanding of what was once called The Negro Problem, as well as his excellent prose style. That style was brilliantly imaged for me on 17 January 1967 at Robert and Dorothy Bones small dinner party in New York City, where I watched:

Closely pursued by a few Black guests at odds with a point in his literary philosophy, Ellison leaned back in his chair, rolled a smoking cigar between his fingers, and like Captain Ahab teasing Starbuck into lower yet, deeper levels of thought, the author of Invisible Man receded, calmly voicing his heavier and heavier defenses, until he seemed to disappear into a filmy cavern suggestive of pure logic. (from The Force and The Reckoning, p. 66).

I have taught The Invisible Man, and my copy of it, with my questions and answers for my students in the margins, might still be in the library of the City College of the City University of New York. I also taught there Richard Wrights Native Son, to which the same comments (concerning margins and location of the novel) apply.

Godelieve Simons has been both an artistic partner and a close friend of yours for the past twenty years. How did that relationship begin? How has this relationship been important to you and to your work? What have you learned from each other?

Godelieve Simons has been both an artistic partner and a close friend of yours for the past twenty years. How did that relationship begin? How has this relationship been important to you and to your work? What have you learned from each other?

Godelieve Simons and I met by chance in 1990 in Liège, Belgium, at the 17th International Poetry Biennial, where I read my essay Writing and the Absolute (which helped calm the audiences rising fever as it joined discussants mired in religious controversy). Knowing herand her mother and brotherhas expanded my sympathies as a Melvillian isolato; and dealing with her as a sometimes complicated artist has both informed and tested me in sometimes unexpected ways. Of course, anything important to me as a Bob Marleyan human is important to me as a poet.

What she has learned from me is a matter you would have to learn from questioning or observing her. She might have learned from me that all people will not always yield to her strength of character, be the issue large or small. I might have learned from her, on the other handbesides some knowledge of engraving and related artthat what one learns gradually about adult behavior should be used, not simply remembered. What I must have learned from Godelieves artist-friendsabout art and about people, too much to summarize heremust give way to a mere listing of a few of their names: Louis Collet, Jacques Demaude, and Elio de Gregorio.

You mentioned that you are working on a poem about Obama. Is there anything you would be willing to say about this poem at this time? Or, perhaps you would just like to express some of your thoughts about our new President.

Since I feel that my poem about Obama will not be completedand thus will have a partial life only in my mindI prefer not to comment on it, leaving it that unseen life free from misinterpretation. As for the real Obama, he is that splendor in the grass that some yet-unmade calendars and documents will fail to grasp: that smoothly political and yet intestinally non-political man who was summoned from worldly success and stationed in a battle zone to ride the new Bucephalus. All that a horse-and-man can do has been seen before, but Obamas Real Ride will be invisible: begun circumspectly, advanced ingeniously, and ended invincibly. This deft, far-seeing man was created to help us move insightfully through a new century, and he will do so.

To the extent that you are willing to talk about it, what other new work or works do you have in progress?

If I have new works on my mind, I have been so preoccupied with catching up and holding steady for several months that my conscious mind has been trying to protect itself by hiding that fact from me. Sometimes I sense criticism from my above-the-ears committee, but I squash it.

What do you think is the most important thing for people to know about you, or about your work?

What do you think is the most important thing for people to know about you, or about your work?

Your first question probably covers what I could say here. The most vital thing for people to know about my work and me is that, as a person, I represent almost everything that has happened to African Americans in and beyond the USA, from the beastly things to the heart-warming things. On the other hand, as a university professor from 1957 to 1984, my life was probably quite different from that of any other African American professor that I can think of.

I calculate that before the Open Enrollment policy, when more African American students entered CCNY because of altered admission standards, an average of 1% of my students were African American. Stated differently but still factually, nearly all of my students were white except for the last two years or so of my career. Strangely, I seldom was aware of that situation while I was on the job, and I do not believe that a significant number of readers of my poetry, or other works, would alter their opinion upon discovering these few facts. In the end, the most important thing to know about a work is how it makes you feelif, indeed, those results should be separated. After all, the whole person writes a serious poem, not just the heart or the heels.

What is the most important thing you learned from Langston Hughes?

My association with Langston Hughes taught me that a writer, especially a poet, ought to be a certain kind of person, aware of the beauty and truth possible in man and his normal environment. The Harlem-based author saw these qualities around him and in the history of African Americans; and he tried successfully, with inborn humor when possible and appropriate, to portray what he saw and knew. I learned from Langston Hughes that a good writer must learn to hit what he is aiming at; and he spelled it out for me when I asked him what his aim was. He said simply, I try to illuminate the condition of the Negro people in America, that racial term being current [at the time]. I witnessed generosity in Hughes, and I benefited from it when he allowed me to rummage through his basementeven while he was away in Paris or elsewhere abroad[looking for precious documents he had forgotten]. Such confidence, which I thought rare, I appreciated.

What about Richard Wright? Did you know him?

Unlike the case of Langston Hughes, at whose desk I could sit when he was in Europe (although I seldom did so), I never saw or talked with Richard Wright.

I wrote to him about my desire to write my doctoral dissertation on his fiction but I received no reply, although I learned that at the time of his death (on November 28, 1960) that he was sorting out exactly the kinds of documents I would have needed for my work. My essay Fever and Feeling: Notes on the Imagery in Native Son (in Negro Digest, XVIII, No.2, December 1968) is my only scholarly essay for publication on Wright. As an ancillary note, I add that I now call his daughter Julia, a writer and speaker on her own terms, a friend of mine.

I found myself standing before a captains desk as the only man in the regiment ineligible for discharge (lacking seventeen days of required service). Were going to send you to Alabama, he said. As if holding back from a death chamber, I replied quietly, By God, I wont go. He paused, seemed to study the double row of ribbons and stars on my chest, while I was seeing again my poem Dark Soldier pinned to the bulletin board of our USA-bound ship. He explained that he could send me to Fort Benning, Georgia, and could add a fifteen-day furlough to the orders.

Did you know James Baldwin? And whether you did or not, what are your thoughts about him and his work?

My single direct contact with James Baldwin came the afternoon at The City College of New York when I introduced him to the audience awaiting his lecture.

I remember using the image of a bridge to connect points in my remarks, which he approved with appreciative nods of his head. The strict brilliance and unflagging directness of his work complement a moral insistence derived, perhaps, from his training for the ministry as a boy and, more certainly, from the inescapable racial injustice, and agonies even, that African Americans must balance in their local environments. Baldwin, in both fiction and prose, has challenged us with a legacy of both fire and fumes.

What did you learn from your mother?

From my mother I learned lessons that did not sink in, perhaps, until years had gone by. Through observation of her I learned the inevitability of hard work and the uselessness of petty complaints, the preciousness of solid character and the honor in reliability and integrity. Even now, I cannot imagine her being truly afraid of anybody or anything. The person in my hard life the most worthy of affection was that lady.

What do you think is important for Americans to learn or understand about our recent history?

I knew an old African American man in White Plains, NY whom I called Denim Cap because of his customary headpiece. He often spoke of his daughter, a grown woman, married, as that kid of mine, removing his cap to scratch his head in puzzlement. But one things sure, you can bet on it: Things change! He would then replace his cap as if collecting a bet. If he were alive today, he would need no college education to comment on recent history, for life had taught him to expect murders by children, President Obama, and lucky surprises. Things change.

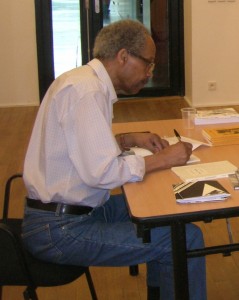

Photo: Gary Lee Kraut, 2011, http://francerevisited.com/

What else should I be asking you? (What else would you like people to know?)

Godelieve Simonss 7 Profiles of James Emanuel (Bruxelles: Gravi Sim, 2006) contains a contributory paragraph about me, in the section on seven people important in my life, written by Marie-France Plassard. She records there correctly that I once told her that she knows more about me than anyone. Forty years of close friendship make that quite likely, supported by our travels to India, China, Thailand, Turkey, Australia, as well as Africa and countries in Europe. In 1970, Marie-France and her mother took me in so that their large house and spacious grounds (Le Barry to the postman in nearby Condom) became my second home. Given the largest room, I wrote much poetry there. Now at this moment of August 6, 2009, when Le Barry is up for sale, although the many books and stacks of documents enclosing me at my desk look almost the same as they appeared a decade ago, I feel that an era has come to an end. As Denim Cap said, Things change. I now imagine him smiling as he says so, and it is a fact that Marie-Frances Paris apartment is within walking distance of mine.

Additional online resources

The Dan Schneider Interview 5: James Emanuel, Sept. 28, 2007.

“Wishes, for Alix” by James Emanuel, from “Writing from the Heart, Reading for the Road,” a blog by Janet Hulstrand.

Janet Hulstrand, “Remembering James A. Emanuel: Poet, Teacher, Humanitarian,” France Revisited, October 2013.

Obituary: “James A. Emanuel, Poet Who Wrote of Racism, Dies at 92,” William Yardley, The New York Times, October 11, 2013.

Photos of the author by Janet Hulstrand, from a classroom visit in Paris in 2008, with the exception of the last one, which is a still taken from a video by Gary Lee Kraut in a 2011 classroom visit.

James Emanuel (June 15, 1921 - September 28, 2013) is the author of 13 books of poems, including Whole Grain: Collected Poems, 1958—1989 (Lotus Press, 1989), a memoir, The Force and the Reckoning (Lotus Press, 2001), and he co-edited with Theodore Gross the highly-acclaimed anthology Dark Symphony: Negro Literature in America (Free Press, 1968). Emanuel was educated at Howard University, New York University, and Columbia University, earning a PhD from the latter. He taught at the City College of New York, the University of Toulouse, the University of Grenoble, and the University of Warsaw.

Janet Hulstrand has taught literature courses in Paris, Florence, Cuba and Hawaii for the Education Abroad program at Queens College, CUNY, "Writing from the Heart" workshops in the Champagne region of France, and literature and culture classes at Politics & Prose Bookstore in DC. Her articles and essays have appeared in The Christian Science Monitor, Smithsonian, and Bonjour Paris. She lives in Silver Spring, MD.