Volume 15:4, Fall 2014

A Splendid Wake Issue

May Miller appeared on The Poet and the Poem on WPFW-FM, DCs premiere jazz and poetry station, many times. This conversation between host/producer Grace Cavalieri and May Miller is from a program in 1987. The sound of Mays voice is in the line, as it is in her poetry. The poems are excised as no rights were obtained for reprint, although two appeared earlier in Beltway Poetry Quarterly, and in those cases links are provided.

Grace Cavalieri

The name of the program is The Poet and the Poem. Im Grace Cavalieri, and with me is Washingtons most celebrated poet, May Miller. If we ask how long she has been with us, she will say, the whole century, perhaps. If we ask what she has done for us, it has been the writing of seven or more books of poetry. She has chronicled our history. She is an authority on the Harlem Renaissance, which actually had its roots right here in Washington, DC. May Miller, beloved friend.

May Miller

I am always happy to read for my dear friend, and anytime she asks, I give. Now if you will lead me just a bit, Gracie, what do you think your audience would like? Should I begin with Birthplace, that I consider birthplace of humankind? Because I am reaching beyond the sex; Im trying to reach beyond racial divisions; Im trying to talk about mankind. And the Federal Poet just published this poem in the fall, and Ive called it Mankind.

Grace Cavalieri

The voice of May Miller. A voice that we have absolutely grown to need and to love. We couldnt be without that voice. This is the voice of poetry, and especially of Washingtons poetry. May, your interests have not always been parochial. Though you have written about Howard University; you have written about your neighborhood; you have written about your constellation, your city, your country, your universe. And your range extends to that of mankind. Isnt that a big piece of cake?

May Miller

Well, Gracie, if I could live up to your expectations, it would be beautiful. Now, I would go back to how I have gone year after year, feeling ancestry. When some friends came back from Kenya, they brought me a little figureI think youve heard me say thisand that poem, Gift from Kenya, has been rather popular, and it traces, of course, my ancestry. I felt that when I touched a little wooden antelope that some friends had brought me, I was touching my own heritage, when I touched the wood. And so I thought that maybe I will read this Gift from Kenya.”

Grace Cavalieri

I might say that you have before you, on the table, seven books of poetry, and this is just a small proportion of your lifes work, we might add; that youve between five hundred and a thousand poems and anthologies in books throughout the years.

May Miller

Yes, probably. Because the first poem, as I told you, was printed when I was 13. And my father told me, when I got a check for twenty-five cents from School Progress magazine, I was never to cash that check. I hope I wasnt dishonest, but I cant find that check anywhere. And it was for twenty-five cents, and it wasnt worth a tin nickel!

Grace Cavalieri

And this book is called The Clearing and Beyond, actually a very well regarded book. With quite a bit of praise.

Reads Gift from Kenya

Grace Cavalieri

It has no end– That is a line which reverberates from your work.

May Miller

And it reverberates from mankind. The progress of man.

Grace Cavalieri

You have seen the progress in the city, from the dawn of the century as you so happily tell us, and you have seen attitudes change, and transform, and transcend your life. But from the beginning, you never felt a division. You never felt, here you are, and there I am. You always have a singularity, which dealt more with the human spirit than it did with racial heritage. Am I misrepresenting you?

May Miller

No, I think you are right, and I can trace that to living in our university community. When I was a little girl, many of the professors [at Howard University] were white. I think my father was probably one of the first black deans at our university. And, really, we were children of the campus. And if a professor spoke to us, we didnt think, Whats he doing speaking to us? No, we were the children of the campus. And I think that we were very fortunate in coming up under a mixed faculty, and all these years people have been people with us. And I glory in that feeling, and I will carry it, hurts and all of that. You have to overlook. You have to know that mankind is able to make mistakes, and you have to realize that you too make mistakes.

Grace Cavalieri

Did you have a very sheltered beginning? Werent you actually raised in a very, very proper and quite Victorian household?

May Miller

Of course.

Grace Cavalieri

With your ruffled petticoats.

May Miller

Of course.

Grace Cavalieri

And you sat upon your starched horsehair sofa with your hands crossed; I can just see you.

May Miller

Yes. My mother, we always said, when she straightened her shoulders and threw her head back, we knew we were doing something wrong! And my father, my mother always said, he whipped the boys with a morning glory vine. He did not believe in force.

Grace Cavalieri

Oh. And through your parlor came the great intelligentsia of the early part of the century. I know that actually there is talk of Langston Hughes and Paul Laurence Dunbar; and these were people who drank tea in your kitchen.

May Miller

Well, Ive always regrettedI think youve heard me say this beforethat I was born a little late for this. But my oldest brother was a baby when Paul Laurence Dunbar came to live in the house. And when he asked my mother, What shall I get the baby? my mother said, Your first book, Mr. Dunbar. And he wrote on the flyleaf of that book a poem to my brother. And I have often said that my brother didnt care for poetry. I should have been born, and that book should be dedicated to me!

Grace Cavalieri

Where is that book today?

May Miller

That book is in a bookcase in my hall. Im going to leave it to one of the libraries who will want it, because he has written on the flyleaf a poem to my brother.

Grace Cavalieri

What are some of the themes that you feel are reflected in your poetry over a lifes work?

May Miller

I love being a member of humankind. And if I dont stress that somewhere, even in love life, in domestic relations, Im not true to myself. And I cant imagine drawing lines where human beings are concerned. Here we are talking about nuclear explosions. How on earth can we do that to mankind? It really is something I dont understand. And I think that in one of these poems, I have sort of reflected that. Now give me a minute to locate it.

Grace Cavalieri

Science is always been a special interest of yours.

May Miller

This is called Anemones. One morning, and I imagine that many of you who may be listening have read the Post, in which there was a statement that the world perhaps had come from nothing, and to nothing will return. That was an awful feeling to read scientific proof that this could happen. And I think that I was so downhearted having read that, I sat on a couch and I looked at the coffee table. At the end there was little bowl, and in it, among the green, was a flower. And I thought to myself, that has some meaning. A little flower, among the green. And I looked at the morning paper in my hand, and then I look to that coffee table, among those greens was little red flower. So I wrote this poem, Anemones, the Prologue.

Reads Anemones, the Prologue.

May Miller

I just want humankind to preserve humankind. I am bothered about racial minds; about racial dialects and that type of thing. Were mankind; were the most precious thing that is on this earth, and weve got to remember that.

Grace Cavalieri

Well, your spirit has always been so much that of the creator, you are incapable of imagining that some people move us toward destruction. It is obscene to you. Whether in the name of politics, or world power, or global power struggles. It is still obscene to you. You become horrified at the thought.

May Miller

Thats right. And I noticed that more and more of the magazines are taking the articles that deal with the continuation of mankind, and I like to read those articles, because I have a hope that mankind will discover that we are the most precious thing on this earth. And we dont know whats on other planets, because the scientists have sent through a hole in the universe a figure of man.

Grace Cavalieri

Was your father an astronomer? Did I get that?

May Miller

Yes he was. He was the first Black student at Johns Hopkins, and it was there he studied astronomy.

Grace Cavalieri

And didnt he engender in you a love for

May Miller

The sky. And maybe thats what is my problem.

Grace Cavalieri

I dont see it as a problem, May. Praying for the continuation of life on this planet, is not a psychological phenomenon.

May Miller

No. No, and it is the theme that really has invaded my poetry recently.

Grace Cavalieri

You also deal with flight as a metaphor, and I think that you have a sense of the marvelous that in this century we have come from horse and buggy to

May Miller

The plane.

Grace Cavalieri

The Concorde. Right. Have you

one of your famous poems about flight

May Miller

I think maybe it is Wings.

Grace Cavalieri

Right. Now what is the title of that book that youre holding?

May Miller

Wings is in this book. And this is Dust of Uncertain Journey published by the Lotus Press. It was first published by Random House long before it was published here.

Grace Cavalieri

This has been more anthologized than all of your poems, and there was a period of time when you were writing a great deal of material about flight. Now this is not the one about Air Florida?

May Miller

When the plane went down over Washington. And this was, oh, 10 or 15 years later after the Boston flight. Because the plane that went down over Washington was in the 80s. I think somewhere that this poem had been reviewed, and they mention the fact that I went back to that first devastating plane crash over the Boston Harbor, because we were very young when that happened. There mustve been early in the 40s that that plane crashed. And you remember reading in the paper that there wasnt any trace what had really caused it, except nature.

Reads Wings.

May Miller

We had, probably, the same problem right here in Washington. Nature seems to rebel every now and again to the intrusion.

Grace Cavalieri

Can you lay your hands on that poem about the Air Florida crash? I think it follows suit. And, flight has been something where you always used a metaphor for what is possible in us, exploring the unknown, and the dangers of tampering with the laws of nature.

May Miller

Yes. Because you see, it was snow that put down that flight over the Potomac. The poem is With the Tide: the Potomac River 1982

Grace Cavalieri

I was on the 14th St., Bridge with my daughter Colleen. Picked her up from work.

May Miller

Reads With the Tide

Grace Cavalieri

May, did you sit with that tragedy inside of you, and then start gathering images to begin that? How did that poem come about?

May Miller

This poem came about when I read the cases of the men that were on the bridge. Now, my nephew was going over into Arlington or Alexandria, and he was passing the Potomac, and he was on that 14th St., Bridge. I think he said around seven cars ahead of him the bridge broke and went to the river. He never knew whether they were saved or not, because he couldnt stop.

Grace Cavalieri

Did you sit down and just write it all of one piece, or did you work on it day by day and do it in segments?

May Miller

No, I wrote it right away.

Grace Cavalieri

May, if we look at your books, and read them from cover to cover, what do we know about your mind?

May Miller

Its awfully hard to know oneself, when writing. You just really dont know, when something says to you, Put that in writing.

Grace Cavalieri

Do you think its a divine calling, May? I know youre too scientific to make outrageous statements, but dont you sometimes feel that youre just blessed with these ideas that come through you?

May Miller

Well, everybody born is blessed with life. And I think that some have a strain that leads towards this in life; another has a strain that leads to a situation in life. So, I dont know, I think all writers write from within. There is something in the end that responds to a situation, to a person, even to an object. So, one cant say.

Grace Cavalieri

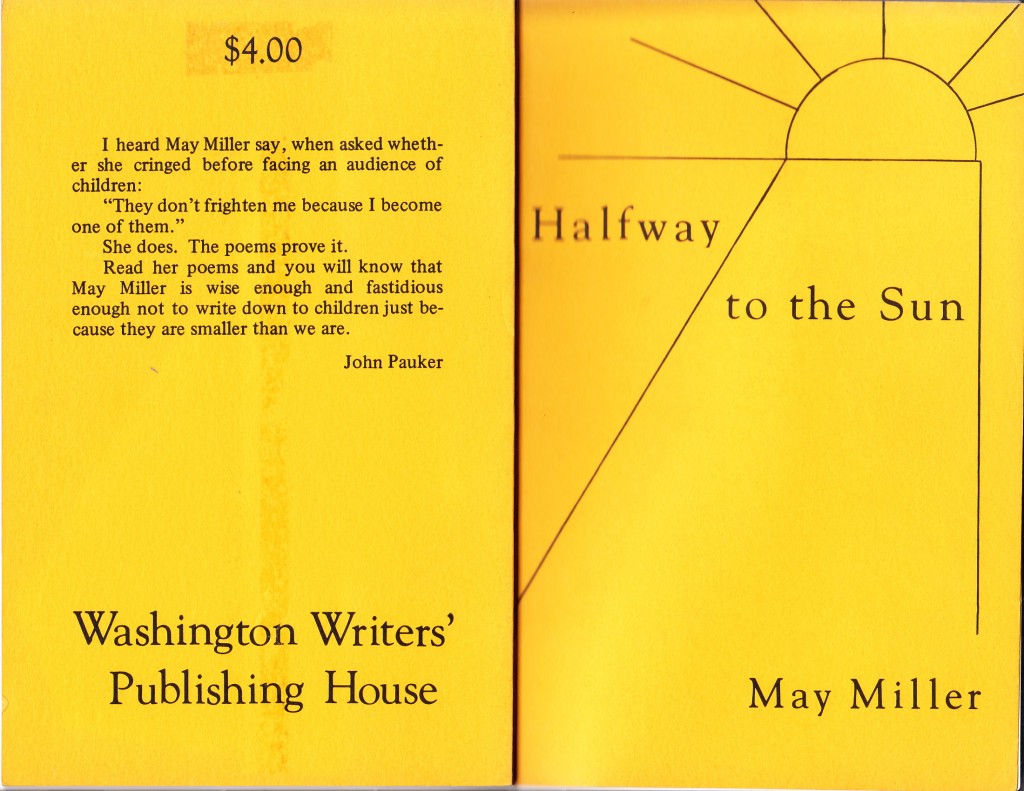

But the deeper the well, the better of the poetry. The deeper the well; so lets go to the well. There is a poem I particularly love, because it is in a book which actually is written for children, but can be appreciated by both adults and children, Halfway To the Sun. And it is a poem, as I recall, about her childhood and sitting outside looking at the stars, and its the story of a frog. But, we also have an adult version. So take us through that historical piece of writing if you will.

May Miller

I think youre talking about “Hummingbird.” Well, when we were kids of course, we lived right there at the foot of the hill sloping down from the campus at Fourth and College Street. And we had trees in the garden in the front. And the little hummingbirdsthe Rose of Sharon bush, I think they called itdid you ever hear that term, Rose of Sharon bush?

Grace Cavalieri

Was it a red flower? They love red.

May Miller

No, they like the trees, the Rose of Sharon bush flowered. They seemed to come to that little tree in the front yard, and my father had said if you can throw salt on the tail, you can hold them in your hand. And theyre so tiny. And I didnt write this poem until adulthood, but I look back. I remembered how we chased the hummingbirds.

Grace Cavalieri

I see that connecting image.

May Miller

Hummingbird. I read somewhere, and Senator Eugene McCarthy said, “Yes, but that hummingbird was cheating you, because he rides on the wings of other birdson the backs of other birds.” But I had read very carefully. I do not write a technical poem without trying to get scientific background. So before I could write the poem on a hummingbird, I got a book on birds, and found out what the Hummingbird could do and couldnt do. So next time I saw Senator McCarthy, I said, You were wrong. They did not cheat, they were really going according to the scientists. He said, I think youre right. But he was the one who questioned whether it was possible.

Reads Hummingbird.

May Miller

That is a book for the children who take the salt in their hands to throw at birds, because that was the idea. If you can get the salt on the tail of the bird, you could catch it. That had us chasing, salt in hand, to capture the beautiful hummingbird.

Grace Cavalieri

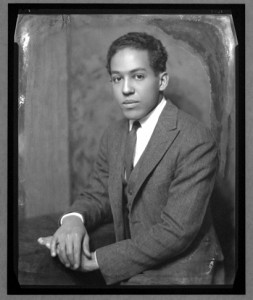

Well, we look back at that era and think of May Miller. Tiny petite May. I can just see you and the people you met. And then your growing up, and then your entering your career as a writer and a young playwright and a teacher. And then we think of your friendship with Langston Hughes. And you knew him as a young bright star, didnt you?

May Miller

I knew Langston when his mother came to the house. We lived in the Langston house, which was a house built by his great-grandfathers brother.

Grace Cavalieri

Where was that, May?

May Miller

Fourth and College Street.

Grace Cavalieri

When you met Langston Hughes for the first time, what was your impression of him?

May Miller

A young man, and his little brother was just a little boy, holding the hand of his mother, and that boy died very early, long before Langston. I think that boy died before he really reached his late teens.

Grace Cavalieri

Did you love Langstons writing?

May Miller

Well, yes. Langston and I didnt always agree on some things, but I was very friendly with him, and I admired him greatly. And I think that he did a great deal for the recognition of Negro poetry, and I have to admire that.

Grace Cavalieri

Now he has the recognition in the whole panoply of Letters, not just in Black Letters.

May Miller

Thats true. He did a great deal to further recognition of Black poetry. But then Langston was broader than race. He stretched his arms out to people.

Grace Cavalieri

Do you feel he was the first person to get the jazz idiom down on the page?

May Miller

I guess maybe, if you call it an idiom. Maybe Langston was the one who captured the recognition of it.

Grace Cavalieri

And Sterling Brown caught the Blues on the page.

May Miller

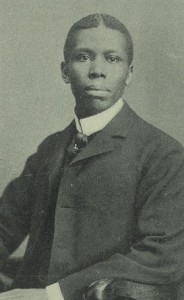

But dont forget that Paul Laurence Dunbar did.

May Miller

Now, Langston dedicated a book and wrote an inscription to my brother, he had it on the title page, and I have the page; I showed it to you once, Grace. He wrote this: Dear Kelly Miller, When I was a kid, I wrote this thats what I did. When you grow up, I may be dead, but always think of what I said. That you grind to make your mark for truth, because, Kelly Miller, our bets are on you. And thats written. I believe I showed you that book, Grace.

Grace Cavalieri

That is terrific.

May Miller

Im going to give that book to the Library of Congress because its written in his handwriting, and signed the year 99.

Grace Cavalieri

Dunbar was the first person to actually use dialect on the page. Did Langston Hughes rely on it as much?

May Miller

No. Langston was more modern than not. Now, he captured much of the lingo of the present Negro, and the street Negro. And I do some of Langstons poems from time to time when Im speaking. And the one he did on Seventh and T, I think I did for one of the TV shows.

Grace Cavalieri

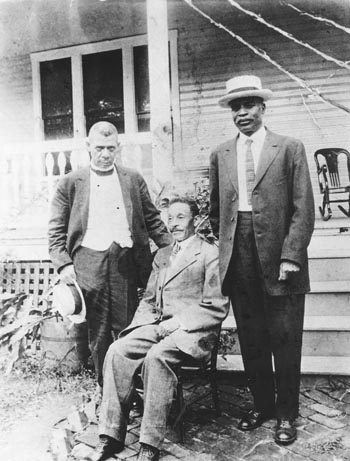

Right. Other great personages have crossed your life; I know that your father, Kelly Miller, knew Booker T. Washington, and was involved with him.

May Miller

That was because he went to Tuskegee to speak on numerous occasions. And then they were together at that school

in West Virginia, and I have a picture. I think you mustve seen that.

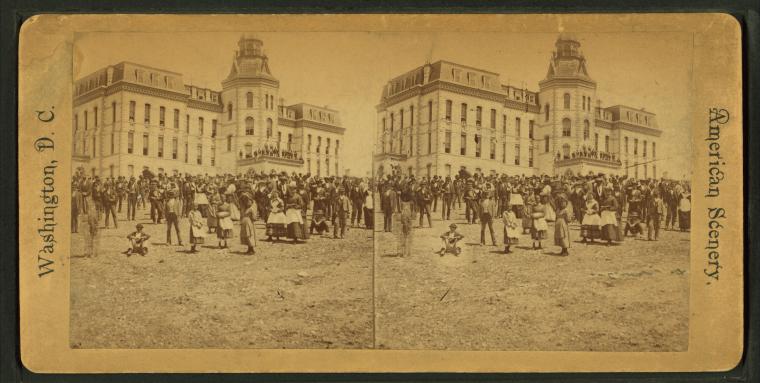

West Virginia Colored Institute, from left to right, Booker T. Washington, school co-founder Byrd Prillerman, and Kelly Miller. Photo courtesy of West Virginia Culture and History, West Virginia Archives.

Grace Cavalieri

Yes. The photo of Kelly Miller and Booker T. Washington.

May Miller

They were speakers at the West Virginia Institute, it was at that time. I dont know what they call it now, but it was on the lawn.

Grace Cavalieri

You never met Booker T Washington?

May Miller

I was a very little girl. My sister was a year and a half younger. But I do remember my father taking us by the hand. He was visiting the Langstons on the corner, and he took us by the hand, he wanted us to be able to say that we had shaken the hand of Booker T. Washington. And I often thought of that when we went over in that same house to live when we were growing up as children.

Grace Cavalieri

These people were friends of the family, and now there are colleges named after them, and busts in the library. What does it feel like to have known the human being which is now the memorial? To have known them for just folks, and to know that they are now historical personages?

May Miller

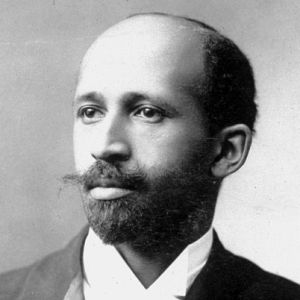

But you see, as children, its fortunate that you really dont know. These are just people, and your father wanted you to say that you had taken the hand of Booker T. Washington. And it was at that time that we shook the hand of Booker T. Washington. And of course W.E.B. DuBois stayed in our home.

Grace Cavalieri

I had forgotten that. Did you think highly of DuBois? Did you have a high opinion of him, and the work he did?

May Miller

Whether you agreed with everything or not isnt the question. And he had a love of children. I have a picture of Yolanda as a little girl that he sent me because I was Yolandas age. And he wrote on that. And I was so stupid; I cut the back of that off and put it in an album, and that inscription that he wrote I dont have, to the little girl whos my daughters age. But I have the picture of Yolanda at that age.

Grace Cavalieri

I forgot you were friends.

May Miller

We were around probably 11 or 12 years old.

Grace Cavalieri

Well, let us hear some more of May Millers work. I love Who will pay my debts when I die?

May Miller

Oh, well now let me tell you about that one. That was two poems. I have one that I do for the children, because they can work it with me and we call it the Frog Choir. We lived there at College Street, and at the end of College Street was a pond. And we as kids would wade in that pondwe were forbidden to take off our shoes and wade. We werent very good children, because thats what we did. And at night when wed sit on the steps, we would hear those frogs croaking in that pond. The pond, I think, is still there, at the end of College Street. The houses are down, and dormitories are up in their places; the steps that we sat on when we were little children, all of that has disappeared. But I think that the lily pond is still there. And then at night wed hear the frogs. I dont take credit for this Frog Choir, because my father recited it to us, and Im sure that that was a part of his heritage from South Carolina

Grace Cavalieri

This is in Halfway to the Sun.

May Miller

Now, this is for children. And then Ill read the version that I later wrote for adults.

Reads The Frog Choir.

Grace Cavalieri

Halfway to the Sun is still in print.

May Miller

And the children recite that with me. They love saying it. And then long after I have finished not I, not I, they keep on saying, not I, not I.

Grace Cavalieri

I know many of those are limited editions and probably out-of-print.

May Miller

This one has gone into a second printing.

Grace Cavalieri

Whats the title of that?

May Miller

Dust of Uncertain Journey, a late book, and this childrens book Halfway to the Sun was printed here by the Washington Writers Publishing House, and its going into a second printing out West. Im very happy about that, because this book may have been circulated on the eastern coast. I like to feel that might touch children in the West.

Pond Lament, is from the adult point of view, remembering when we did those things, you see.

Reads Pond Lament.

May Miller

You see, this is from the adult point of view. You look back, and you say, That was true. Wholl pay my debts when I die?

Grace Cavalieri

Theres a very serious undertone in that, and its about release. Its about letting go, and its about a kind of relinquishing which we should learn to do long before we get to our death.

May Miller

Well, now, would you want me to end the reading with a love poem?

Grace Cavalieri

I would love a love poem.

May Miller

All right. Well, I was thinking of the book, I think maybe The Dust of Uncertain Journey, which I dedicated to my husband.

Grace Cavalieri

I must say that all the poets in Washington remember him very well, because he used to bring you to the readings.

May Miller

Yes, and he used to say, Now look, I will take you to the reading, and I will stay there and take you home, if you need me. Now if you feel you dont need me, maybe Ill stay home and look at a football game.

Grace Cavalieri

May Miller is her name, the history of Washington is in these poems.

May Miller

And then let me read the one, The Washingtonian, after I read this one. Im going to read two. The Old Vow Repeated. All of you married people who may have an ear to the radio today, remember this.

Reads The Old Vow Repeated and Death Is Not Master.

May Miller

I think you ought to hear The Washingtonian, because Im very proud of my city. Im proud that I was born here, reared here, the whole darn business here!

Grace Cavalieri

You are Washington, lets face it.

Grace Cavalieri

When you walk down your own street, what must you think from the changes that you have seen in Washington? From the Victorian houses, and the grand places where you lived, and now it seems so congested. And now it seems such a huge metropolis. What do you feel about the city, having seen it in all of its phases?

May Miller

I cannot give up hope. I must not. I must hope for the generations to come, that there will be a deep appreciation of the beauty of this city. I really worry when I see some of the old buildings torn down, and the concrete and glass taking their places. But that I guess is progress. And Im always happy when they preserve one old building.

Grace Cavalieri

I know that your father gave quite a bit of his estate to Howard University.

May Miller

He did actually, because he was afraid with five children and five mates, that Howard would never get it if it were left to them. So, he saw to it that Howard got that.

Grace Cavalieri

And quite a bit of property was the Miller property. And now the girls dormitory is on that property is that right?

May Miller

…is on that corner. Well, remember that was the old Langston house. Thats how my father came to that house, when old man Napier went back to Tennessee. That was the last of the original Langstons in town. So they sold the house, and my father got it and we were young then, and that front porch was a lovely thing. We watched the cars go by up to the reservoir, and wed sit on the porch swing when the young men were visiting from the campus, and you had your dreams then. “Come Morning.” Suppose I read that?

Reads Come Morning.

Grace Cavalieri

Her name is May Miller. Her poetry is forged out of belief, and faith, and hope, and love, and it has made her the first lady of poetry. The name of the program is The Poet and the Poem. I am Grace Cavalieri. The station is WPFW in Washington.

Grace Cavalieri and The Poet and the Poem now celebrate 37 years on public radio. The series is recorded at the Library of Congress and distributed nationally via the Pacifica Network.

Grace Cavalieri's newest publication is What the Psychic Said (Goss Publications, 2020). She has twenty books and chapbooks of poetry in print, and has had 26 plays produced on American stages. She founded and still produces "The Poet and the Poem," a series for public radio celebrating 40 years on-air, now from the Library of Congress.. She received the 2013 George Garrett Award from The Associate Writing Programs. To read more by this author: Grace Cavalieri: Winter 2001; Introduction to "The Bunny and the Crocodile" Issue: Spring 2004; Grace Cavalieri on Roland Flint: Memorial Issue; Grace Cavalieri: Whitman Issue; Grace Cavalieri: Wartime Issue; Grace Cavalieri: Evolving City Issue; Grace Cavalieri: Split This Rock Issue; Grace Cavalieri on Ann Darr: Forebears Issue; Grace Cavalieri on "The Poet & The Poem": Literary Organizations Issue.

May Miller (January 26, 1899 - February 8, 1995) first came to prominence as an award-winning playwright during the Harlem Renaissance. A high school teacher, Miller was active in the famous literary salon of Georgia Douglas Johnson, and later held salons in her own hom, using Johnson's as a model. Miller helped establish the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities, serving as Chair of the Literature Panel for the Commission's first three years. From her retirement from teaching in 1943 until her death in 1995, Miller dedicated herself to writing poetry, publishing nine books of poems, including Dust of Uncertain Journey (1975), Halfway to the Sun (1981), and her Collected Poems (1989). To read more by and about May Miller: Myra Sklarew on May Miller: Memorial Issue May Miller: DC Places Issue May Miller: Audio Issue