Mark Strand was the fourth U.S. Poet Laureate (serving from 1990-1991 at the Library of Congress). This interview was held at the Library of Congress on January 22, 1991 and was originally published in the March/April issue of the Writer’s Center Carousel.

>>>

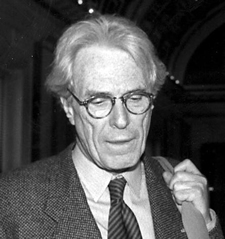

Photo: Library of Congress

Nordhaus: How does it feel to be Poet Laureate/Consultant in Poetry of a state which seems to be at war?

Strand: Well, my thoughts clearly are confused. The war is new and I find myself watching it on TV both in horror and astonishment at the technological virtuosity we display. Part of me is thrilled by it…but, then, it’s so removed—you’re getting an edited version of the war thrice removed, pictures that were taken in a moving aircraft transposed to another medium. What it does is create distance…

Nordhaus: On the subject of distance…your first three books: Reasons for Moving, Darker, and The Story of Our Lives, appeared during the Vietnam years, and yet—with a few exceptions, they contain little direct reference to the war. I wonder whether surrealism isn’t, in itself, a form of resistance. In the context of Eastern European poetry, for instance, surrealism has been viewed as a response to political repression.

Strand: That’s not necessarily true. Surrealism isn’t the only way one has of resisting. For instance, the Italians at the time of fascism wrote hermetic verse. Surrealist poetry initially was revolutionary. It wasn’t an opposition to direct repression. It had to do with the cumulative repression of the literary canon.

Nordhaus: What about psychological repression—in “Eating Poetry, ” those dogs in the basement?

Strand: Yes, that’s interesting. When I wrote that poem, I wasn’t sure what I was writing about. It took me weeks to figure it out, and you’re right—psychological repression is a feature of that poem. The dogs are the self that would be liberated. They are the animal, impulsive, uncontrollable elements in my nature, especially in my appetite for poetry. The librarian represents something—more polite, conventional. Probably my mother!

Nordhaus: Throughout your work, there are mirrorings and reversals. I’m thinking of poems like “The Man in the Tree, ” or “The Tunnel, ” where identities are confused or reversed, in later poems like “The Story Of Our Lives” and “Reading in Place, ” where the distinction between the poem and the world it supposedly reflects is confused or blurred.

Strand: It’s not really a confusion. In the earlier poems, in “The Tunnel” for example, I’m talking about two parts of the same person working on each other. In “Reading in Place” the reality of the reader plays against the action of the poem. The poem’s action presents another reality.

Nordhaus: In “Itself Now ” the poem becomes a metaphor for human life.

Strand: I guess it’s related to the fact that I’m a reader. Reading is all I do. And I’m not a particular or discriminating reader. I don’t go to the movies. I don’t go anywhere. Reading is my whole life.

Nordhaus: Some of the other poems in your new book, poems like “Narrative Poetry” and “Translation, ” take on intellectual and critical issues and attempt to enact the processes they discuss. The undertaking is audacious; the danger is that such poems can become emotionally remote.

Strand: Yes. It’s hard to discuss these issues in a diction that isn’t academicized. I try to do it in a playful and palatable way, to embed it in a humorous context, the human context of our everyday lives.

Nordhaus: Can you talk about the formal impulses in the new book?

Strand: Two-thirds of the poems in the book were in rhyme and meter in rough drafts. I started out writing in forms. The early poems were rhymed and metrical. The book I’m working on now will have very little prose; two-thirds of the poems will be in rhyme and meter—couplets, sonnets. It’s fun to do. The lines will continue to be long: a long and languorous line with a lot of internal rhyme and assonance. When you’re rhyming short lines and the rhymes occur with too much frequency, the poems become very song-like. It’s not a sound I feel I should capitalize on in my poetry; it tends to trivialize. Also, the longer the line, the more time you have to prepare for the rhyme.

Nordhaus: I wanted to ask you about the significance of the title, The Continuous Life. The book is a departure from and at the same time a continuation of your earlier work, and it comes after a ten-year hiatus.

Strand: That wasn’t intentional, but, of course, it can have all kinds of meanings. It’s the title of a poem in the book, not I think a representative poem, but one that many people—many non-addicted readers of poetry—liked. And, then, it seemed sort of positive. I have this desire not to appear—overly dark.

Nordhaus: I’ve always wanted to ask about “The Untelling.” The obsessive, repetitive structure of that poem creates such enormous emotional tension. The Freudians talk aboiit “screcii incinories “— imagined scenes that have the compelling quality of tneniories—and I’ve wondered if something of that sort isn’t at work here.

Strand: The event itself is conjured up. It’s not a real moment, but a mixture, a conflation of moments. It’s about the impossibility of capturing the reality of the past, the impossibility of getting to the truth in language. The poem the narrator is attempting to write is ambitious. It’s in blank verse. It tries to recover a moment in the past, to get the moment to enact itself again, but it fails. One can’t get to the truth.

Nordhaus: “The Untelling” also reminds me, somehow, of Elizabeth Bishop‘s “The Waiting Room.” Both poems focus with so much intensity on a particular moment ofa child’s coming-to-consciousness.

Strand: All, but that’s a great poem. She has such enormous economy and restraint. I don’t know how she does it. [“The Untelling”] is all about failure. It’s a fumbling poem. I wouldn’t write those poems [in The Story of Our Lives] now. At the time, I couldn’t have written them differently. I was so much in the middle of all that material. I guess they wouldn’t be different if I were writing them now. But they’re not poems I care for now, not the kind of poems I like to read.

Nordhaus: What about “Shooting Whales”—which was a little later, I think.

Strand: I think that’s one of my best poems—because there’s a synthesis of lyrical and narrative elements; the lyrical component is not overwhelmed by the awkwardness—the klunkiness of narrative. And the narrative isn’t interrupted by lyrical digressions. Narrative is so linear and predictable. What’s difficult is to find the blend of lyricism and action that will produce an energized narrative progression.

Nordhaus: I know you originally planned to be a painter. Can you talk a little about the switch from painting to poetry?

Strand: I was an art student at the time, at Yale, but I’d lost interest in painting, and I started taking English classes. I’d been drawing since I was twelve or thirteen. It was assumed in the family, and by my teachers, that I’d be an artist someday. But when I got to Yale and spent time around real painters, I knew I wasn’t. I was looking at other people’s work and didn’t have a vision of my own. I didn’t have a vision of what I wanted.

Nordhaus: And did you, when you started writing?

Strand: I wanted to sound like Wallace Stevens, like Federico Garcia Lorca, whoever I was reading at the time. I tried to duplicate what they did. I’d diagram their sentences, reproduce their stanzas. I was fascinated by their poetry, but I didn’t understand it. Your ability to understand poetry increases with the effort you put into your own poetry. The young read in a superficial way.

Nordhaus: You worked very hard.

Strand: I was insane, crazed, wholly absorbed. I led a charmed life at Yale. I lived in the L. and B. Library. I had no money. I worked at Mory’s, delivered laundry. My last year, I taught freehand drawing. My first poems were about painting—they appeared in the Yale literary magazine. I had a year between graduation and my Fulbright to Italy, and I’d discovered the direction my life would take.

Nordhaus: What kind of family did you have? Clearly they encouraged your interests in art and literature.

Strand: Books were the most important things in my household. My parents were middle-class Jewish intellectuals, but of an odd stripe. My father, though he was Jewish, grew up in a Catholic orphanage. He left the orphanage—and school—when he was in the fifth grade; but he read widely and learned languages and had a lively mind. He was smart, a great story-teller, animated. My mother was born in New York City, but raised in Quebec. Her father was a brilliant linguist. He was chief censor for the Canadian government during World War I. He knew Lithuanian, Latvian, the Ruthenian languages; he translated the letters of prisoners of war. My mother was very beautiful and artistic, somewhat reserved. She studied art, and later, when my father’s business took us to Latin America, she became an archaeologist.

Nordhaus: And what did they read? Did they read poetry?

Strand: My parents read little poetry, but they remembered the poems they’d learned as children. My father used to say he read as a way of reaching places that he couldn’t scratch. He’d memorize what he read, Francois Rabelais, pages and page of it, prose, and poems, too. He was—how shall I say this—he was a willing prey of rhetoric. It was a way in which he entered into rapture. Also, they read for information. Remember, my parents were living through the depression in a time of political uncertainty. They were Communists in the early thirties and then left the party. People with such uncertainty built into their lives cling to prose, to non-fiction.

Nordhaus: And what kind of reader are you?

Strand: I read to steal. Also for rapture, for transport. I learned to read late and was left back half a year in the fifth grade—because I was in another world, a day-dreamer. And I was interested in sports; I couldn’t stay inside. At 16, that changed. I became bookish. By 18 or 19, I’d struck a kind of balance, but I always felt I had a lot of catching up to do.

Nordhaus: The general reader doesn’t read poetry nowadays.

Strand: I don’t think poetry reveals itself quickly enough for the general reader; and, remember, poems are about a great many things at once, including their relationship to other poems.

Nordhaus: What are your thoughts about aging and writing? Do poets improve as they mature?

Strand: You feel you can do better; you have more skill, experience, whatever, but what you write doesn’t have the energy, the spark. Take William Wordsworth, for example. The 1850 “Prelude” is slightly better written than the 1805 version—but the 1805 “Prelude” is more powerful, a little less graceful. The good thing about getting older is that you’re not as ambitious, you’re able to risk more. You feel greater existential certainty about your being, but, then, you’re not as free as you are free to be, because you’re bound by years and years of using words that have become your words, writing in a manner that has become your manner. One has the authority to experiment but would have to reconstruct a new self in order to write the new poetry. The poems in The Continuous Life—they may look different, sound different, but they’re still my poems. I suppose if I wrote a book on raising cabbages, it would still sound like my book.

Nordhaus: Since so many of our readers attend writing workshops, I’d like to ask for your views about teaching poetry.

Strand: I like teaching, in moderation. I like it best when I do little, but I do like doing some of it. I don’t have much use for workshops. Workshops can be destructive and painful if they’re good. If they’re bad, you don’t learn anything. When I teach, nobody hands in their own poems. I give assignments that isolate particular problems—aspects of sentence structure, quatrains, couplets. That way we can suggest changes, and it doesn’t hurt so much. The assignments create distance.

I teach a course in Experimental Writing. We look at great beginnings and endings of novels—for the intensity of invitation, the degree of resolution, etc. I give the students 15 chapter titles, and short novels are written over the course of the class. I also teach a course in European Short Fiction—Jorge Luis Borges, Heinrich von Kleist, Nikolai Gogol, Franz Kafka, Italo Calvino, and Milan Kundera. Also, Donald Barthelme. Barthelme is a writer I feel very drawn to.

Nordhaus: Has your position at the Library of Congress been good for your writing?

Strand: I’m just starting to write again now. It’s been a year since I’ve written. I’m working on a big poem, part verse, part prose, called “The Posthumous Valley.” It’s a post-apocalyptic vision. The closest thing to it I can think of is the movie “Road Warrior.” The poem is about a band of people who enter a burned out city—civilization—but they can’t stay. And then they meet another band who turn out to be themselves…

Nordhaus: Earlier we talked about reversals of identity ansd mirrorings in some of your earliest poems. We seem to be back at the beginning.

Strand: Yes, but on a larger scale, a much, much vaster canvas…

Originally published in Volume 10:4, Fall 2009.

Jean Nordhaus has published five books of poetry, most recently Memos from the Broken World (Mayapple Press, 2016) and Innocence (Ohio State University Press, 2006). She has published work in Prairie Schooner, American Poetry Review, the New Republic, Poetry, and Gettysburg Review. Born in Baltimore and a long resident of Washington, DC, Nordhaus has coordinated poetry programs for the Folger Shakespeare Library, been President of Washington Writers’ Publishing House and served as Review Editor for Poet Lore. To read more by this author: Five Poems, Vol. 5:4, Spring 2004