by Wynn Yarbrough

Poetic Ancestors: Volume 13:4, Spring 2012

May not have the glitter or the glamour of L.A.

May not have the history or the intrigue of Pompeii

But when it comes to making music and sure enough making news

People who just don’t make sense and people making do

“Washington, DC,” Gil Scott-Heron

The loss of Gil Scott-Heron last year was a loss for an international commmunity of fans and activists, but also for DC in a more specific way. Gil Scott-Heron’s presence in Washington, DC included his collaborations with Brian Jackson, most notably Winter in America, recorded at D&B Sound in Silver Spring (1973). Scott-Heron also played Blues Alley and the Cellar Door, as well as taught at Federal City College, which later became the University of the District of Columbia (UDC). He lived in Northern Virginia (on Martha’s Road) as well as in the District (on 16th St. just below Malcolm X Park). One of his most famous works, The Bottle, was inspired by a scene outside a DC liquor store.

The loss of Gil Scott-Heron last year was a loss for an international commmunity of fans and activists, but also for DC in a more specific way. Gil Scott-Heron’s presence in Washington, DC included his collaborations with Brian Jackson, most notably Winter in America, recorded at D&B Sound in Silver Spring (1973). Scott-Heron also played Blues Alley and the Cellar Door, as well as taught at Federal City College, which later became the University of the District of Columbia (UDC). He lived in Northern Virginia (on Martha’s Road) as well as in the District (on 16th St. just below Malcolm X Park). One of his most famous works, The Bottle, was inspired by a scene outside a DC liquor store.

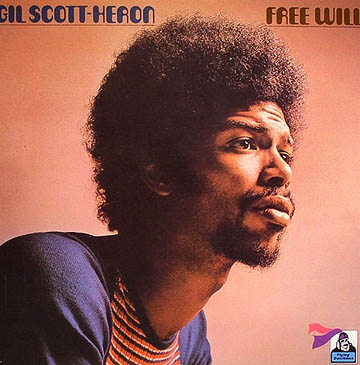

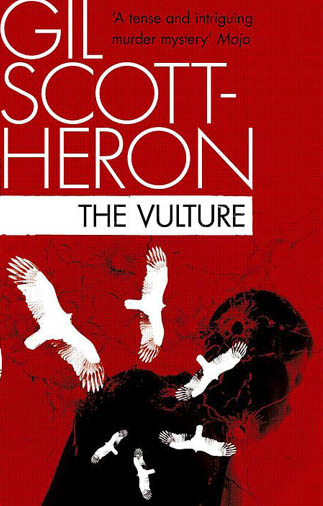

Born in Chicago in 1949, Scott-Heron spent his early life in Tennessee and then moved to New York. He attended the Fieldstone School as a scholarship student and enrolled in Lincoln University, following in the footsteps of one of his idols, Langston Hughes. He went on to earn a Master of Fine Arts from Johns Hopkins University, but his formative years at Lincoln University were productive. He met his future musical collaborator, Brian Jackson, as well as writing two novels, The Vulture (1970) and The Nigger Factory (1972). But he really began immersing himself in music and fusing his signature poetics with blues and jazz music, modeled after The Last Poets, a musical group which featured percussion and jazz scored with spoken word. Central to the lyrics was a political consciousness that Scott-Heron emulated and would hone in his own development as a writer. Education, consciousness, and discipline would be hallmarks of Scott-Heron’s artistic life in both writing and spoken word through the 70’s and 80’s. He recorded twelve albums, featuring the likes of Ron Carter and Brian Jackson (with whom he formed Black and Blues) before a hiatus in the mid 80’s. He toured extensively throughout his career, and had finished his last album, I’m New Here, just before his death in 2010.

“I believe in ‘Spirits.’ Sometimes when I explain to people that I have been blessed, and that the Spirits have watched over me and guided my life, I suppose I sound like some kind of quasi-evangelist for a new religion. … I believe. . . to paraphrase Duke Ellington, that at almost every corner of my life there has been someone or something to show me the way. These landmarks, these signals, are provided by the Spirits.” (from The Last Holiday)

His literary and artistic influences were many: Langston Hughes, Sterling Brown, Jean Toomer, Countee Cullen, Claude McKay, Richie Havens, John Coltrane, Otis Redding, Jose Feliciano, Billie Holiday, Malcolm X, Huey Newton, and Nina Simone (to name a few). His art encompassed blues forms and techniques (he called himself a bluesologist), the legacy of the Black Arts Movement (artistic representations calling on aesthetics more representative of the African-American experience, including, but not limited to, oral poetics, political and social consciousness foregrounded in the piece), as well as his targeted focus on American politics and racial history with a searing examination of popular culture as an expression of problems with class and race in America. His literary influence will be a lasting achievement; he is featured in both The Cambridge History of African-American Literature and The Norton Anthology of African-American Literature. He’s well represented in both anthologies, and scholars repeatedly examine his use of the blues, both structurally and thematically, as it is linked to his combining jazz rhthyms and tonal structures in his spoken-word art.

His literary and artistic influences were many: Langston Hughes, Sterling Brown, Jean Toomer, Countee Cullen, Claude McKay, Richie Havens, John Coltrane, Otis Redding, Jose Feliciano, Billie Holiday, Malcolm X, Huey Newton, and Nina Simone (to name a few). His art encompassed blues forms and techniques (he called himself a bluesologist), the legacy of the Black Arts Movement (artistic representations calling on aesthetics more representative of the African-American experience, including, but not limited to, oral poetics, political and social consciousness foregrounded in the piece), as well as his targeted focus on American politics and racial history with a searing examination of popular culture as an expression of problems with class and race in America. His literary influence will be a lasting achievement; he is featured in both The Cambridge History of African-American Literature and The Norton Anthology of African-American Literature. He’s well represented in both anthologies, and scholars repeatedly examine his use of the blues, both structurally and thematically, as it is linked to his combining jazz rhthyms and tonal structures in his spoken-word art.

Critics read Scott-Heron’s legacy in different ways. Indeed, so did he. He shrugged off the mantle of godfather of hip hop. Though many have claimed him as such, this is not only reductive, it ignores many other developments in musical history and Scott-Heron’s roots in the blues. Tony Bolden, in his essay “Blue/Funk as Political Philosophy: The Poetry of Gil Scott-Heron,” sees many different aspects of art and politics at work in Scott-Heron’s oeuvre. Signification, call and response, short riffs surrounded and embedded by internal rhymes and shifts in rhythm, manipulation and play with grammar are just a few of the techniques Bolden attributes to Scott-Heron.

“Words have been important to me for as long as I can remember. Their sound, their construction, their origins.” (from The Last Holiday)

Whether he was exploring The Ghetto Code (Dot Dot Dit Dit Dot Dot Dash) and language at its most musical and sound based or as in H2O Gate Blues, where he signifies and unwraps, layer by layer, post WWII American history and iconic images and cultural references (Vietnam, Boeing, Bobby Seale, Richard Nixon, John Wayne), Gil Scott-Heron’s work revises the blues into new musical explorations with a consciousness that reflects the awakenings of the Black Arts Movement. As E. Ethelbert Miller has contended, You see the Black Aesthetic at work in Gil’s art. He maintained the political content (Steiner show). While rap artists follow the money and may even be aware of the dangers of the constant message about politics, Scott-Heron didn’t sacrifice the political at the expense of his aesthetic.

In a New Yorker profile on Scott-Heron, Alec Wilkinson contends that rap’s origins include an intersection of “d.j.s in the Bronx, among African-Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Jamaicans, in the summer of 1973, and especially with a d.j. named Kool Herc. The people involved were going to parties where they could dance to a spare form of recorded music that had been arranged so that the pulse was foremost. While elements of rap are evident in Scott-Heron’s work, the idiosyncratic nature of his art resists a specific genre categorization. Or as Jack Hamilton posits in Transition magazine, One of the reasons Scott-Heron gets subsumed into the tradition of rap music is because no one quite knows where else to put him, and there has been a tendency to see African American popular music of the last fifty years as essentially bifurcated between rhythm and blues and hip-hop, with jazz drifting about as a sort of quirky and aloof third party. Gil Scott-Heron might fit into all of these genres, and he also might fit into none of them.

“Our codes and slang terms that slip easily in and out of vogue go from addition to meaningful exchanges of emptiness and impotence rather quickly as people and music and moves and what-means-what to us and each other goes in and out of style in the blink of an eye.” (from The Last Holiday)

This past summer, Scott-Heron’s spirit was summoned in district on separate occasions. The DC Poetry Festival changed its name to The DC Poetry Festival Honoring Gil Scott-Heron, and Scott-Heron turned up at the Capital Fringe Festival. Faruq Hussein-Bey‘s The Revolution Will Not Be Televised dramatized the spirit of the singer/poet in seven short stories for the stage. For those who still feel the loss of a international musical/poetic force and voice, Scott-Heron left behind an autobiography, The Last Holiday: A Memoir (Grove Press, 2012) and I’m New Here, an album released by XL Records in 2010. If Scott-Heron’s life was a battle, I’d like to think it was one he drew passion from but also a battle which enabled him to shine, with all of his talents as well as his shortcomings: in short, measured like a talented artist who raged against the dying of the light. As he sang on his last album on a song entitled, Your Soul and Mine:

So, if you see the vulture coming

flying circles in your mind;

Remember, there is no escaping

for he will follow close behind.

Only promise me a battle

for your soul

and mine.

Bibliography

The Last Holiday, 2012 (memoir)

Now and Then: The Poems of Gil Scott-Heron, 2001 (poems)

So Far, So Good, 1990 (song lyrics and poems)

The Nigger Factory, 1972 (novel)

Small Talk at 125th and Lenox, 1970 (poems)

The Vulture, 1970 (novel)

Gil Scott-Heron (April 1, 1949—May 27, 2011) is the author of two novels, three books of poems, and a memoir. But he is perhaps best remembered as "the grandfather of rap," the spoken word performer whose recordings in the 1970s influenced later generations of hip hop and soul artists.

Wynn Yarbrough lives in Mt. Rainier, MD and teaches Children's Literature and Creative Writing at the University of the District of Columbia. He is the author of a book of poems, A Boy's Dream (2011), and his work has appeared in Black Zinnias, Potomac Review, The Pedestal, and Poetry Midwest. He is book review editor for Interdisciplinary Humanities. To read more by this author: Wynn Yarbrough: Spring 2012