Tactile

The father does not hug his son long enough.

The son carries his suitcase upstairs, unpacks

neatly, hangs shirts, slacks, jacket, belt.

Return, routine eases the gut-punch of grief,

but he washes his face quicker than before,

turns off the bathroom light, tries not to see

his grandmother accidentally trapped in her basement,

banging on the door as hard as a 91-year-old woman

can before collapsing. He sets the alarm, tries

to imagine shaving and ironing the next morning,

instead of Oma’s frenzied calls to Aunt Peggy,

the brass handle’s stubborn immobility,

frantic thuds growing louder, quicker, quiet.

He climbs into bed, curls up, cries briefly,

but without tears—in this house grief

is the bust of his dead stepmother sculpted

by the father who never worked in clay, the son’s

poems about that stepmother, who asked the Lord

for “two good years” with Earl and died twenty five

months later. Grief comes to this house

through the hands, and this week grief will

debone chickens, slice the collards and red onions.

Grief will iron black ties and white shirts, design

the funeral program, sift photos for the cover.

September

In the middle of a sentence of advice, the first wave

takes his legs, salt water conspiring with the diabetes.

For the first time you see your father fall.

Sitting on the wet sand, his legs covered with the surf,

he laughs. It’s genuine, not the uneasy, self-deprecating

chuckle he used to relate the story of the day last summer

when he wet his pants. The next wave comes as he’s

struggling to stand up, gripping the hand you’ve extended

and as this wave takes him from your grasp you feel a little

of what it might be like when he slips more finally away.

The wave rolls him towards the beach and he comes to rest

again, this time on all fours and not laughing. His hair

is damp, white with sand. He sputters water from his mouth.

And before he tries to stand again the wave recedes,

taking him with it. You stand in front of him, stopping

him with words you thought were made only to be spoken

back: “I’ve got you.” Then the sea relaxes, lets you help him up.

Part of you feels proud, like you’ve passed a test. Part of you

wants to fall, let him pick you up once more. Later,

when you watch him stretched sleeping on the blanket, his

confession of feeling “helpless” still echoes uncomfortably.

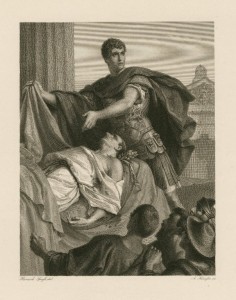

Anthony and Caesar’s Body, print by Alfred Krausse, undated. Courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Presence

Dirt on the boots we wore to dig the hole.

Hairs collected in the vacuum a month ago.

Pet store receipt for diapers.

Unstolen food on the dining room table.

Unclaimed food under the dining room table.

Loose hair in broom bristles.

The quiet delivery of mail.

Oatmeal shampoo on the shelf in the laundry room.

Lamb and chicken blend in the pantry.

The chewed up tennis ball under the couch.

The chewed up tennis ball behind the bookcase.

The chewed up tennis ball in the coat closet.

The chewed up tennis ball in the toy box.

Hairballs in places we haven’t dusted yet.

Sympathy card from the vet’s office.

Walking downstairs alone at 5:30am.

Recession

Pity the pig farmer

who witnessed the gaping maw

of opened earth, Hades enveloping

Persephone disappearing quickly

leaving doubt of his presence,

save for sulfuric stench, absence

of the young woman who had just returned

the farmer’s sow. This man knew loss:

When Demeter arrived—already inconsolable,

instinctively aware of her child’s vanishing—

he remembered his wife’s miscarriage, seasons

of her flat belly, an infant lost to a disease

the doctor couldn’t name. But what

could he say to the Goddess descended?

Struck by her beauty, her despair, his mouth

worked silently, finding no words that might

warm the air already turning frigid.

In the coming months farmers

who learned of the story cursed his slow

steps, his inability to save Persephone

and their fields. They were, like him,

at the whim of the Gods. They suffered

the unpreventable famine, waited for Demeter

to negotiate the return of their prosperity.

The Front

Cracked summer afternoon.

Brutus broods outside.

His tent offers only brief

respite from heat, grief, regret.

The sand’s only solace:

mirage of the fallen risen.

Riding, Cassius replaces

Caesar’s image, greed

shoves aside greeting.

Through quarrel and

bluster Brutus clings—

what should have been

is all he has left save

Lucius—the lute he plays

brings sleep, desert night,

promised reckoning.

Hayes Davis holds a Masters of Fine Arts from the University of Maryland; he is a member of Cave Canem's first cohort of fellows, a former Bread Loaf working scholar, and a former Geraldine Miles Poet-Scholar at the Squaw Valley Community of Writers. His first volume of poems, Let Our Eyes Linger, was published by Poetry Mututal Press in April, 2016. His work has appeared in New England Review, Poet Lore, Gargoyle, Delaware Poetry Review, Kinfolks, and several anthologies. He teaches English at Sidwell Friends School in Washington, DC, and lives in Silver Spring with his wife, poet Teri Ellen Cross Davis, and their children. To read more by this author: Four Poems (Winter 2007); "America" (Langston Hughes Tribute Issue, Winter 2011).