First Books IV

Volume 16:2, Spring 2015

After College

Riding my bike to work in the dark before cars

flood the streets with their headlights,

I think a lot on molecules, cells

and vibration, wat it is to be warm,

and what nature is, of Being, in a freezing

universe, its four oclock and Im the first one in.

I wet the tables, haul sacks of flour

through the open loading dock,

and clouds of steam light up

in miniscule dawn over the grey landscape

of the concrete floor, where I stand

in floured cotton, immense and groggy.

I watch the sky expand over the trees.

The oven smokes. Ive burned

my priming batch, but I save

one loaf. Inside its dark-charred crust

the bread is moist. I eat a furtive breakfast,

leaning my head against the doors black glass.

At the Forge After an Argument

At the Forge After an Argument

At last the coal inside my head has all

burned down to coke, and I am cancellous,

soot-black, I am intemperate. The skin

of my head pulses as I hammer out

an umber bar, the clangor injuring

the ear and freeing it from indenture.

I have only the one iron in this fire,

and heat pours into it until it glows

past white, spits sparks, and sublimates, lit motes

rising and starring the barns dark-mattered air.

I carry on until whats left is slewed

past useful form, a curl of steel seeming

to grasp for what I cannot ever have

again: the blacksmiths blank, wife-bodied soft.

On the Way to Catoctin

Morning comes up thick

in the grass and thatch

and sumac of the woods verge,

carried up the way a bird

rides a thermal up,

over endless hills, phone lines,

and roads, over the heat map

of lives reclaimed from sleep,

rising into color, blanketing

the blue land in a mosaic

of reds, dense in grids

and looser elsewhere,

internal monologues spooling up

from dreams halting

states, old arguments rehashed

in the space under

the showers heat, separate

and brief and self-contained.

Unwaiting, the light continues

its plain growth, articulating

houses eaves and the certain

green of bracken uncoiling

into spring, over trees

ghosted with color, over the hills

various opacities, the verdigris

of lichens breaking down the mountains

folds, and back into the clearing, into the drum

of my heat beating, pulse thin

and lifting, getting up from the discomforts

of my bed, and getting going.

I dont know hw many lives I passed

on the way to Catoctin,

there was rain and more

rain, I saw ground soft and green

with winter wheat, or broken

to rough crumble, a blurred

paintwork, canvas-coarse.

On the way to Catoctin, I looked

down new-laid asphalt-black

to future slums, fine vinyl townhomes

built four stories up, piebald

in partial brick, red hillsides

held in check with stacks

of concrete blocks, suppurating mud,

so much of all of this for sale,

so much foreclosed, so much arrayed

in palletized rows, ready

for the forklift-up, the truck-hoist-up

the rise of smoke from chimneys, steam

from valleys, the heron from the overgrown

retention pond past which the red roads

merge and flow, a sough of cars

from somewhere close to somewhere

else, each river-noise

muted and eased

into the rest. I knew

the world could not possibly be so large

as to offer such repetition,

and to require so much distance

for return; and yet it was,

and did, and I pulled

off for gas and closed my eyes,

my head usual and heavy.

Up ahead the fallow fields

and the harrowed fields lapped

against the rise of the earths folds,

and there, without the highways speed

and blur, the roads of my childhood

seemed about to appear, connecting

to the fragment I was on, standing by the car,

holding the pump full open and staring up

into the skys straying

Silver, steam rising from the coffee

in my other hand, motions unrandom

but unknowable, limned with the earths ring.

The Pleasures of the Alphabet

1. Summer

It is mid-August, and the dust and fire-smoke

give way to rain, not for an afternoon,

bt for two long otherworldly weeks:

verdant, English, biblical.

Out through the wide double doors

the rain lays the ash leaves flat,

the road is black, and clouds rise

from the ragged folds of mountainsides.

Even in the mountains the world sums

to flat: fields and fences

average out; the scrawl of rocks;

the phone lines gentle catenaries.

In all of this a woman laughs on her phone,

standing under a juniper, in the lines of rain.

2. Fall

Letters grow like fruit,

pendant and discrete; words

form without syntax, just color

or scent without context.

When vowels fall, they drop quick

striking the ground and rolling

among the incomprehensible blades of grass.

Still, sense remains, up in the branches.

When consonants split the whole tree shakes,

and creaks, and shoots curl clicks, the old wood

checks and the new wood breaks.

And then wind uncreates.

In the stream beside the tree

the letters rattle and collect.

Languages come to be and pass,

and there is something else, to small to see:

The dappled shadows move, coalesce

and disperse, a broken place, delayed

sky, makeshift gestalt, well-hid

half scented idea-of, dark shuttling

manifold signsthough thrown

by letters they almost seem alive,

and so believe themselves the cause

of whole unfallen sentences.

3. Winter

The streetlight holds a world of snow,

whole genus of pictographic script,

and though each flake participates in soundlessness

somehow the gist comes clear.

4. Spring

Vines on the porch swell at the bud-scar.

A ladybug crawling on the glass.

The pertinence of pleasing things

does not last.

In the dry garden

new snow creates a page

under old writing.

Truman State University Press was established in 1986 to publish peer-reviewed research and literature for the scholarly community and the reading public. The Press publishes 14 to 18 books each year and has over 200 titles in print. The T. S. Eliot Prize for Poetry is an annual award for the best unpublished book-length collection of poetry in English, in honor of native Missourian T. S. Eliots considerable intellectual and artistic legacy. The purpose of the T. S. Eliot Prize is to publish and promote contemporary English-language poetry, regardless of a poets nationality, reputation, stage in career, or publication history.

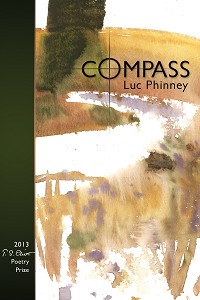

Luc Phinney is the author of Compass (Truman State University Press, 2013), winner of the T.S. Eliot Poetry Prize. Phinney teaches at Johns Hopkins University, and lives in Takoma Park, MD and Missoula, MT.