Volume 17:1, Winter 2016

Some Of Us Press Issue

Waiting

I’ve no idea, sense of place,

where you might be when you stare out

across this crowded bar. Your eyes

have found some space I can not see:

rooms you’ve slept in, long streets,

the face of a man you’ve met here before.

You keep your head down, look up only

when the sound of the door opens

or closes over the song someone has played

three times. In ten minutes

you’ve pulled the blue plaid cuff

of your shirt sleeve twice to check the time.

It’s late. I could tell you that.

We wait, stall for this person

we believe—tell ourselves,

write in letters to distant friends—

will walk in, sit down, and turning

hear the words we find in our hands.

After the Rent

On payday, after the rent

and checking off of other cares,

Dad would bring mother

a box of Schrafft’s assorted candy

or flowers coned in his right hand—

the wrapping paper thin,

vulnerable as the orphan

in the sheer brown of his eyes.

Wordless, nearing thirty-four,

he’d stand before her

like a small boy

watching the Richmond sky clear

for the first time, saying:

“Mama, these are for you.”

My Aunt

My Aunt Mary,

steeped in the Blessed Virgin,

brewed tea twice from the same bag;

hanging them in the kitchen window

while the war raged across Europe.

Pictures of her uniformed sons

and a small choir of nephews

stationed the cross in every room.

Religious,

she worked at the Old Shrine store—

dusting the Infant of Prague

during slack hours.

Some Of Us Press authors gathered regularly for readings at bookstores, especially The Community Bookstore, owned by Dave Marcuse, and Folio Books, managed by Doug Lang. Both were in the Dupont Circle neighborhood. At the Community Bookstore, Marcuse had an upstairs room that was used for meetings of anti-war groups and others. Once a week, on Mondays nights, it was the site of a reading series, called Mass Transit, where Cox became one of the organizers and a favorite reader. The rules, according to Michael Lally, were clear: “First of all the readings were open to anyone, but they had to read their own work, or at least the work of someone who was present, could read no more than five minutes and no one could comment on what anyone else read. We sat, or lounged, mostly on the floor, in a circle…[it] was a well mixed group spanning several generations, the youngest were in their teens and the oldest, as far as I knew was in his seventies, and it was about equally male/female with gays and lesbians and African-Americans and several handicapped poets as regulars.” According to Joan Retallack, “The open readings were a self-selected version of the street scene come indoors. There was intelligence, commitment, intensity, quirkiness, craziness, generosity, egomania, imitation, experimentation, mediocrity, moments of great wit, even brilliance. Numbers might range from 12 to 100.” This group also produced a journal, Mass Transit.

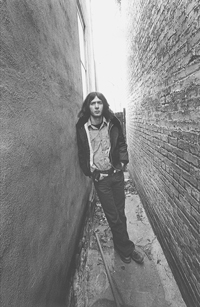

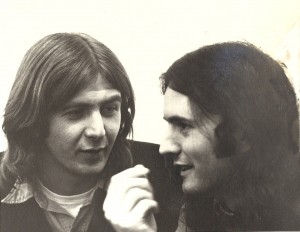

Ed Cox (1942 – 1992), a DC native, spent his entire life in the city, with the exception of four years in the US Navy. Cox was a political activist, and active in the Mass Transit reading series in the 1970s and 80s. Cox taught poetry workshops in battered women's shelters and senior adult housing, and edited two anthologies of his students' poems, Seeds and Leaves (1977), and Some Lives (1984), as well as publishing two books of his own, Blocks (Some Of Us Press, 1972), and Waking (Gay Sunshine Press, 1977). His Collected Poems (Paycock Press, 2002) was published posthumously. Cox graduated from Archbishop Carroll High School, then studied for one semester at the University of Maryland. He worked for the US Association for the United Nations High Commission for Refugees, and helped to found DMZ GI, a coffeehouse for Vietnam War veterans seeking counseling and information about anti-war activities. Raised Catholic, he stated in an interview with E. Ethelbert Miller, “My biggest struggle has been the conflict between what does it mean to be a homosexual in terms of a lifestyle and what does it mean in terms of the spiritual life for me.” Cox was influenced by poets of faith such as Ernesto Cardenal and Thomas Merton, and read widely about philosophy and theology. Of the DC poetry scene in the 1970s, he said, “We found a means through Mass Transit magazine or Some of Us Press to publish cheaply, and in an attractive way, good works of poetry that might not be on many bookshelves beyond Washington, DC but at least they would be available here…I think the thing holding us together was we were all products of an intense period of history in this country, and of conflict and tension and trying to find out what was on the other side of the coin about being human—outside of being a worker, student or father. And there were so many things coming into question—race, sexuality, women’s rights, militarism—that people, I think, felt an acute sense of isolation and did not know where to go with their anger and frustration. Suddenly you could get together in a room every two weeks and have people reading and talking about their work. You could have some guy flip out and sit there and yell for half an hour. Yet he could sit there and yell and no one was going to tell him that he was any less valuable than the person who could read three wonderfully-written sonnets who had studied in England for two years. There was something really good about that.” He continued: “I feel my task as a poet is to somehow make connections between what is real and what is my own particular struggle to become and be a person…I feel that as a poet there is a way, somehow, for me in the poem and in language to talk about human dignity, about people’s righteous anger against basic human needs being taken away from them and ultimately the basic right of life being taken out of their hands. And the only sense of hope that I can feel is if I use my creative life in some way to try and say no to that type of insanity.” Cox died of a stroke at age 46. To read more about this author: Richard McCann on Ed Cox: Memorial Issue, Fall 2003; and E. Ethelbert Miller on Ed Cox: Profiles Issue, Fall 2006