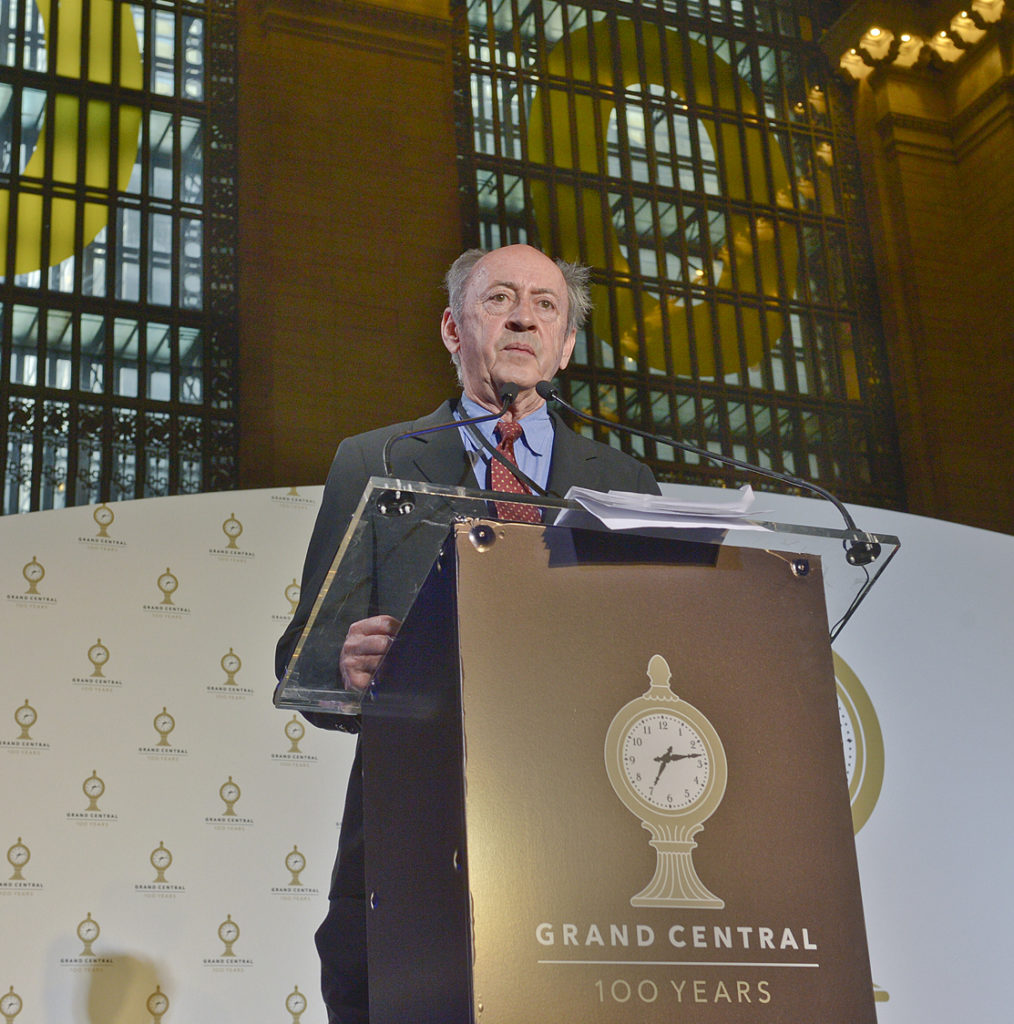

Billy Collins served as U.S. Poet Laureate from 2001 to 2003. Excerpts from an interview that took place at the Library of Congress in December 2001:

Grace Cavalieri: I’d like to hear about the poem you read last night, “Snow Day,” and then talk about your personal agenda.

Billy Collins: “Snow Day” is about that time when it snows so much that the day is declared by some official to be a snow day for schools, and then our lives change in a certain way.

Cavalieri: The audience last night laughed and cried out loud. The tears were coming out of my eyes last night because of the mournful humor of your voice as you made that litany of those nursery school names, some of them imagined, some real…

Collins: All of them are from a phone book! And I started writing that on a snow day, and they were closing schools, and that started the poem going. I kept listening to the radio, but, they were saying like P.S. 47, and Allentown High School, so I went to the phone book and looked under daycare, and nursery schools, and I took all of them, even the Peas and Carrots Day School, I took them out of the phone book. You know they say that if you look in the phone book under Beauty you will find many many listings, but if you look under Truth, you will find nothing… but if you look under daycare, you’ll find all those schools.

Cavalieri: We’re in for quite a year here at the Library of Congress. I have to speak about last night. How many thousands were there? More than one thousand. Here we have this one room on the sixth floor of the Library of Congress Madison building. It was quite filled before the busloads tooled up to the door, and more people came in, and they came in, and they came in, and they broke down walls, not the students, the Library took down the walls, opening the room; and it was the most wonderful audience. Were you surprised—although it was very responsive—were you surprised at how the high schoolers were not quite sure they were allowed to laugh out loud? Did you get that feeling?

Collins: Yeah …

Cavalieri: They were a little restrained.

Collins: I always get that feeling. Well they haven’t been, usually as high schoolers, they haven’t been to many poetry readings, and certainly poetry, the sound of it, I mean it makes you feel like, a little like you’re going to a chapel, or a serious, deadly serious cultural event, and you’re supposed to be on your best behavior. People assume there’s a kind of hushed etiquette about a poetry reading, which doesn’t really need to be the case.

Cavalieri: It was a warm group though. Did you get anything back from them?

Collins: Oh sure. I mean usually when I give a reading, because some of the poems provoke laughter for some reason or other, I’m usually trying to modulate, I’m trying to mix serious poems with lighter poems, and I’m trying to create a mix of the two facets. I don’t want it to be just amusing, and I don’t want it to be too much gravity and I would say that really is a guiding principle for the way I compose poetry.

Cavalieri: I think so.

Collins: I mean for me the perfect poem, and probably this is one of the things that makes me keep writing poems—is that maybe someday I’ll write this perfect poem. I know I won’t, but, the perfect poem for me would be a poem in which at any given point, the reader would have no idea whether the poem is serious or funny, and all of my poems are failures in the attempt to achieve that, because they either err on the side of sentimentality and seriousness, or on the side of amusement and lightness.

Cavalieri: That’s actually not true at all. You have a mournful humor. Your humor is very tragic to me. It’s a very lonely humor. In fact even a listing of those nursery schools in a snowy day makes you have the ache of the light in the kitchens. I’m very interested in how tragedy is like comedy.

Collins: Well, I think it was an Irish writer who said that tragedy is just insufficiently developed comedy; and it was Vladimir Nabokov who said—when he started teaching in America at Cornell—he was being falsely self deprecatory—but he said, “I only know two things, I know that life is beautiful, and life is sad, and those are the two things I know.” And I would add that life is funny. I think poetry is basically expressing, if poetry would express those things simultaneously, I think that’s maybe an aim for me. To express the beauty, the sadness and the sheer ridiculousness of life at the same time.…

Cavalieri: We talked about the high schoolers that were here last night, and you have your own wish to make poetry of significance in high schools. So tell everyone about that.

Collins: Well, what I’ve started to do as Poet Laureate is a program I’ve called Poetry 180, and 180 stands for the roughly 180 days of the school year, and it also signifies a kind of turning around, to poetry, you might say. The idea is to have a poem read every day in American high schools as part of the public announcements, so that at the end of the public announcements, that would be the best place I think, there would be a poem. And I’m choosing 180 poems, hand picking them. Poems that I think high schoolers will be able to get right away, and that’ll have some immediate resonance for them. The aim here is to make poetry for high school students a feature of daily life, and not just something to be studied, and that’s why I want to encourage teachers to get with the program. And they can do that just by going to the Library of Congress web site and they’ll find the poems there early next year; that’s 2002. But I’d like to discourage teachers from bringing the poems into the classroom and teaching them as they would the other poems in the curriculum. I really just want students to hear these poems, and not have to study them, or write about them, or think about them in a public way. I just want them to simply take a poem in every day. And I’m hoping; my sense is, if a student hears a poem every day, there’s probably one poem out there, at least one, for every student. All it takes is one poem to get you hooked.

Cavalieri: It follows, somewhat, in the national consciousness, where Robert Pinsky put a poem on The News Hour, and, you know, if you ask the regular Joe on the street, if he watches it, oh yeah, he remembers that, but he may not recall the poem. The fact that it was there, that a poem was on The News Hour, and is forever an indentation in our minds. You’re following the idea that a poem can be read in a school over the PA system is not at all outrageous.

Collins: Right. Well, it’d be part of the public announcements, so you’d hear that the volleyball team has a practice at 4:30 or whatever, then you’d hear the poem. It’s putting the poem in a kind of unexpected place. It’s a little like Poetry in Motion which puts poems on busses and subways, and as you said, a poem popping up on television. We expect to find poems in classrooms and anthologies, but I think when a poem ambushes us, and pops out from an unexpected place or time, it has more of an immediate effect on us.

…

Collins: When you realize that the human sensibility is something that ties us all together, despite our individual eccentricities, and that, when you must take into account the sense that human beings have a thoroughly limited range of feeling—we feel separation, we feel joy, we feel grief, but there is a limited number of things we can feel. And history has recorded the way human beings have registered those feelings for thousands of years. So, to read poetry returns us to a community of feeling, and a history of feeling. And that, I think, acts as some consolation to our personal feelings. Because when we feel, when we are emotional, we feel alone, I think.

Grateful acknowledgment to Grace Cavalieri and Forest Woods Media Productions’ “The Poet and the Poem” for permission to print this interview.

Grace Cavalieri's newest publication is What the Psychic Said (Goss Publications, 2020). She has twenty books and chapbooks of poetry in print, and has had 26 plays produced on American stages. She founded and still produces "The Poet and the Poem," a series for public radio celebrating 40 years on-air, now from the Library of Congress.. She received the 2013 George Garrett Award from The Associate Writing Programs. To read more by this author: Grace Cavalieri: Winter 2001; Introduction to "The Bunny and the Crocodile" Issue: Spring 2004; Grace Cavalieri on Roland Flint: Memorial Issue; Grace Cavalieri: Whitman Issue; Grace Cavalieri: Wartime Issue; Grace Cavalieri: Evolving City Issue; Grace Cavalieri: Split This Rock Issue; Grace Cavalieri on Ann Darr: Forebears Issue; Grace Cavalieri on "The Poet & The Poem": Literary Organizations Issue.