by Andrea Carter Brown

Poetic Ancestors, Issue 13:4, Fall 2012

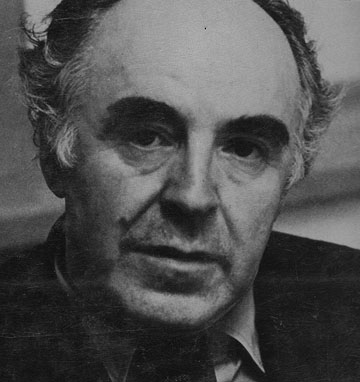

Photo: Mara Politsky, from the back cover of The Poet’s Art

An open window high over Washington Square. Near the back of a college lecture hall, a student daydreams. Her thoughts are interrupted by the voice at the front of the room reading from William Carlos Williams‘s Paterson, You lethargic, waiting upon me, waiting for / the fire and I / attendant upon you, shaken by your beauty // Shaken by your beauty . // Shaken.

Gone, in that moment, the wandering thoughts about who knows what. She turns her eyes to the speaker. He doesnt read, he inhabits the lines Williams wrote about the city where she was born. She is glued to her seat. The words wash over her, the whole class (fifty students at least, perhaps seventy-five) is riveted by the lines their teacher recites. The rest of the world vanishes. They too are standing in that Paterson room with the doctor/poet; they see the patient/woman through his eyes.

Compact, muscular, benevolent, slightly tousled, Professor M. L. Rosenthal holds the entire room in his sway. The year is 1971. He has been teaching poetry at New York University since the late 1940s. He will continue to teach it until his retirement in 1985. Previously that semester, he introduced the class to Thomas Hardy, Gerard Manley Hopkins, W. B. Yeats, T. S. Eliot, W. H. Auden, and Wallace Stevens. He reads the poems they are studying with a deep resonant voice, naturally, not mannered or stilted, more conversationally, with intimacy, gravity, irony, or humor as the poem might ask, with an Irish lilt or an English accent, as the poet himself might have heard his own words. The student does not appreciate at the time how unusual this is.

The textbook they are using, Chief Modern Poets of Britain and America, Fifth Edition, lists M. L. Rosenthal as the third of three editors. She only understands much later that this means her professor has done the lions share of the work. Scattered throughout its pages are her notes in pencil taken during his lectures. Over time, these notes have faded. The dust jacket, despite being much mended, is falling apart. She certainly has not yet begun to realize that this anthology is the product of a life-long immersion in modern poetry, as is his masterful teaching. She had no idea then that she will hold on to this volume through a divorce, remarriage, and half a dozen moves, including one cross-country. That this book will survive 9/11 when it was coated with dust and ash from the fallen Twin Towers. That she will return to this anthology when teaching poetry to college students herself.

Over the course of his long career, M. L. Rosenthal did so much to advance poetry that it is hard to tease apart his many roles. Besides being Professor of English at New York University for over fifty years and the founder of the Poetics Institute there, he was a literary critic whose assembled articles and reviews, collected in Our Life in Poetry, amount to over five hundred pages. In a review of Life Studies by Robert Lowell for The Nation (10 September 1959), it was Rosenthal who first used the term confessional. He was also a pre-eminent scholar of Yeats, Ezra Pound, Eliot, and William Carlos Williams, and the editor of works by these poets. At the same time, Rosenthal edited several important poetry anthologies (in addition to the MacMillan textbook mentioned above) and was Poetry Editor for long stretches at The Nation, The Humanist, and Present Tense. A selected list of his publications appears at the end of this article.

What the undergraduate taking Modern British and American Poetry I in 1971 did not know, would not learn for many years however, was that her professor, M. L. Rosenthal, was also a well-published poet himself. The following year, 1972, he would publish his third collection of poetry, The View from the Peacocks Tail. All told, he would publish six collections of poetry, beginning in 1964 with Blue Boy on Skates, and ending with As for Love: Poems & Translations in 1987. His full-length poetry collections were published by Oxford University Press; one limited edition chapbook, She, was originally published by BOA Editions. Widely respected by his fellow poets, who praised the collections in reviews, it is unfortunate that Rosenthal chose not to include his own poems in the anthologies he edited, especially given the growing role of anthologies in introducing readers to poets. This means that his poetry collections languish in university libraries largely undiscovered by the current generation of readers. Similarly, during his lifetime, internet publishing was still so rare that Rosenthals poetry is not available digitally. The very few exceptions include individual poems in the archives of The Nation.

>>>

If you asked most people, M. L. Rosenthal, professor, critic, editor, poet, was the quintessential New Yorker. And you would be right. After all, he worked his entire adult life in New York City. His three children were born there. He and his wife, Victoria, lived their entire adult lives there and in nearby Suffern, NY. Their two surviving children still live in the area.

And yet, just as many New Yorkers come there from other places, M. L. Rosenthal was one of these.

Macha Louis Rosenthal (Mack to his friends) was born in Washington, DC, in 1917. He was taken very quickly to nearby Mount Rainier and Brentwood [Maryland], as he recollects in his essay, Notes Toward an Unauthorized Autobiography. By the time he was five, his parents had divorced, his mother had remarried, and he moved with her and his step-father to Woodbridge, CT, a suburb of New Haven. The rest of his childhood, the family moved around quite a bit due to the Depression and his step-fathers work as a house painter. After Woodbridge, they lived in Boston, Newark, Cleveland, and Chicago, where he went to college. After earning a B.A. and M.A. from the University of Chicago, he took a job teaching soldiers in Michigan during World War II. By 1949, Rosenthal had moved to New York City to get his Ph.D. at New York University. He would never leave.

Even though Rosenthal lived only the first five years of his life in the DC area, he continued to spend summers and the Christmas holidays visiting his father, who remained in Brentwood, and with his mothers family in Baltimore. The areas impact on him was deep and enduring. In the autobiographical essay, he describes being rewarded for reciting poetry, My father gave us kids a nickel every time we recited a poem. A poet who was a friend of his one day told him: You mustnt do that. Theyll grow up thinking there is money in poetry. Somewhat later, he recounts, My first memories of Whitman, in fact, come . . . from hearing him recited in Yiddish translation by Jewish poets whose tone and gesture were strongly influenced by Russian Futurist mannerisms and Mayakovskyan declamation. To me, in effect, he was a Jewish poet named Voltvétman, who was part of a Russian-Jewish movement of the twentieth century.

The impact of his parents divorce permeates Rosenthals poetry with a sense of loss, and he often writes of the love he continued to feel for both his parents, together with his despair at their no longer being together. Of a childhood prize from this period, he writes It simply disappeared into the worlds storehouse of lost childhood possessions and hopes, like the tricycle, and the trip to the circus that never happened, and the restoration of the Eden I had shared with my parents. These specific subjects appear in his poems.

The son of somewhat bohemian Jewish immigrants with little formal education who spoke Yiddish at home, Rosenthal acquired traits which would define him as a poet from both his parents. His father, who became an Orthodox Jew after the divorce, instilled in his son a deep respect for learning, a fondness for philosophical and dialectical discussion, an innate skepticismthis last perhaps unintentionally. From his mother he learned optimism, a faith, even, in the face of disheartening experience, in the beauty of life. Many of his best poems are haunted by her as a source of enrichment. One of his more charming poems about their combined legacy appears at the end of Poems 1964-1980 under About the Author:

The left-handed child of divorced parents,

What could he do but make

every triumph a mares nest

and all delight a stammering mistake?

The unassuming humor of this poem, coupled with a whimsical wisdom, are typical of the way Rosenthal writes about deeply personal subjects.

All three of his parents (including his step-father) were politically left. Though not officially a red diaper baby, he belonged to that generation of children of radically liberal and highly political parents. Wars, disasters, genocide figure in his poetry. Rosenthals essay On Being a Jewish Poet is a masterpiece which connects personal anecdote and aesthetic considerations with historical issues. In this essay, Rosenthal observes, No doubt Jews have a special memory and awareness engaged with the prophetic tradition that suffuses their whole sense of life and language. And the Holocaust is ours in a way that no Gentile would want to steal from us. . . . there are all the kindred memories and associations of Jews the world over almostthe synagogue and its worlds of thought and reverie, the shtetl, idiosyncratic turns of exaltation and vulgarity, vision and deprivation. But a Jew may write about sunlight on a Sussex hillside, or about love in a way that does not echo the Song of Songs. If his non-Jewish poems are good enough, then lo! they have willy-nilly added to the sum total of Jewish poetry. Looking over his earliest work, he is surprised how more much of it is on explicitly Jewish themes than I had remembered. In subsequent collections, this material comes more to the fore.

The poem which best embodies these preoccupations for me is The Gate. Although this poem dates to Rosenthals first collection, Blue Boy on Skates, published when he was 47, its themes resonate throughout the rest of his work. Written in five sections of a single spare quatrain each, this poem has haunted me ever since the first time I read it. I immediately understood its central situation: the speaker goes out into the night, looking for something cherished. While wandering the foreign streets (whether due to the dark or for other reasons is unclearand unimportant), the speaker unwittingly crosses over into a world in which past and present simultaneously exist. The past world, that of his ancestors, and specifically his father, becomes real for the speaker; the parallels between then and now are both comforting and painful. There is no easy resolution.

The Gate is a deceptively direct poem. I could quote almost any single line, and there would be nothing poetic about it: the diction is conversational, even flat; there is no enjambment or rhyme; there is no regular meter. Yet, a line (or two) from each section will illustrate the poems evocative power: It is not so dreadful after all and I will teach you a trembling grace (from Part 1); I did not know where I was going (from Part 2); Strange that not until tonight / Have I seen the stars in all their silence (Part 3); Love broke their backs, but so long ago (Part 4); I did not know of the gate, my dear. / I did not know. I did not know (Part 5). The poem ends on a note of suspended comprehension and imminent loss.

In his notes about this poem in On Being a Jewish Writer, Rosenthal elaborates that the speaker went out to find his son but found, as well, the immense universe and in it the unforgotten world of the dead. Especially, he found his father, who, he now sees, also passed through the gate once, perhaps in search of the speaker. He goes on to insist, however, I should not force my private associations on the poem. They are merely part of the background of its feeling, though conceivably the sense of being in an alien universe and coping with a devastating break between generations is presented in images and phrasing with some Jewish resonances. This leads to a further observation: The tragic sense of irrevocably disappearing communion between the generations is a deep American motif because of all the constantly dissolving continuities of our complex and ever-changing culture. . . . each poet will use it and change its bearing to accommodate his own inner reality.

For an poet deeply familiar with the cadences of Auden, Eliot, Williams, andabove allYeats, finding ones own voice and gestures as a poet might well be especially daunting. The voices in ones ear make their way onto the page. Unconsciously and consciously. Echoes, homages, to the poets he revered appear through Rosenthals body of work. Small scale and large. There are poems in historical forms. There are references to the imagery and subjects associated with the poets whose work he knew so well (swans, towers). There are poems in dialect and Old English. There are nursery rhymes and nonsense verse (three poems in Blue Boy on Skates originally appeared in The Nation under the pseudonym M. Riddle). There are parodies, odes, ballads. There are many invented nonce forms. However, even when poetic references are apparent to a reader less intimately familiar with his sources, Rosenthals poems are never imitations. The references are always put to his own very individual purposes. Rosenthal constantly weds high to low; the idiosyncratic, specific, contemporary (images and word choices) to historical allusion and elevated diction. In Footnote, an extended prose poem meditation prompted by William Carlos Williamss The Sea Elephant at the end of Blue Boy on Skates, Rosenthal writes, And here is a pretty thought: That the poem is a putting out of the soul to scavenge. To believe even this, one other belief is required: in the soul. More than any other subject, Rosenthal wrote of lovefor others, present and past, especially his wife, mother, and children, of his attachment to this world, of his passionate engagement with the creative life.

Throughout his long career, Rosenthals work explores human history. His guarded belief in the ability of people to transcend their differences through literature, especially poetry, would take him to Germany (1961), Pakistan (1965), Romania, Poland, and Bulgaria (in 1966, when such visits were rare), Israel (1974), Italy and France (1980) as a Guggenheim Scholar, a Visiting Poet, and with the US Cultural Exchange. These visits were in addition to extended stretches in London and Ireland. Late in life he was translating Catalan poetry into English. Other translations are scattered throughout his body of poetry.

Closer to home, one of Rosenthals last professional projects was as Guest Editor of Ploughshares Works-In-Progress Issue from Fall 1991. At 74 still actively engaged in writing poetry himself (he included an unfinished sequence of his own), Rosenthal convinced writers to let work out into the world while it was still being written. The list includes many poets who will go on to have impressive careers, including such an eclectic roster as Charles Bernstein, Eavan Boland, Robert Dana, Tess Gallagher, Rachel Hadas, Donald Hall, Sam Hamill, Brenda Hillman, Thomas Kinsella, Molly Peacock, Mark Rudman, Charles Tomlinson, and Barry Wallenstein. Additionally, he asked each poet to write about the specific work included. This is M. L. Rosenthal at his creative, mentoring, and critical best. And a treat, I must add, for any contemporary poet to read.

>>>

That girl near the back of that long-ago classroom daydreaming out the window was, of course, me.

Looking over my undergraduate transcript, I realize it was not spring, but fall when I took that course. Call it, in retrospect, poetic liberty that twenty years later when describing a moment I thought I remembered vividly, I turned fall into spring for the transformative power of that moment in my life.

There must have been 75 students in that class. Multiply that by the number of times M. L. Rosenthal taught just that one course. Multiply that by the other courses he taught over his long teaching career. Add to that the number of students who used his anthologies, read his criticism, translations; the readers and writers who read the poems he chose as editor; those who knew his own poetry, from journals and collections. Add the expanding community of scholars whose lives were graced by his gifts. For how many of us was the seed scattered in that classroom, in those volumes, to become a life-changing experience? Not so long ago, The New York Times Sunday Book Review frequently published author queries. Will anyone who studied with M. L. Rosenthal at NYU between 1950 and 1985 please contact . . . If such a notice were still possible, the response would be huge. And fascinating.

As for this one student, when I finally found my way to writing poetry twenty years after that course with him, one of the first poems I wrote (but never published) was about that experience. It closes:

Beautiful Thing, you will lie there

Forever fixed in the humble awe

Of the poet. The doctor

Could not help you

As the teacher, reading

His words, does me. Beautiful

Thing, for you I lay down

My pain and weep.

How many others are there like me? Many, I suspect. Weunknown to ourselves at the time, unknown to him for the most part foreverare the beneficiaries of M. L. Rosenthals many gifts.

He shared his wide knowledge not to make writers of us, but to communicate by demonstration the power of the word, the transformative poem of poetry to move, heal, inspire sympathy, teach. For isnt it that to which we all aspireas writers? As human beings?

This was NYUs great gift to me, and many othersto give M. L. Rosenthal an enduring professional home, and to give us a teacher of poetry who made poetry come alive, who lived the creative life and by doing so, communicated a spirit of openness and generosity by which I still try to live today.

Poetry Collections by M. L. Rosenthal

Blue Boy on Skates (1964)

Beyond Power: New Poems (1969)

The View from the Peacocks Tail (1972)

She: A Sequence of Poems (1977)

Poems 1964-1980 [New and Selected] (1981)

As for Love: Poems & Translations (1987)

All of the above were published by Oxford University Press, with the exception of She, which was originally published as a chapbook by BOA Editions and later included in Poems 1964-1980.

Selected Critical Works and Translations by M. L. Rosenthal

Exploring Poetry (with A. J. M. Smith)

A Primer of Ezra Pound

The Modern Poets: A Critical Introduction

The New Poets: American and British Poetry Since World War II

Randall Jarrell

Poetry and the Common Life

Sailing into the Unknown: Yeats, Pound, and Eliot

The Modern Poetic Sequence: The Genius of Modern Poetry (with Sally M. Gall)

The Poets Art

Our Life in Poetry: Selected Essays and Reviews

Running to Paradise

The Authentic Story of Pinocchio of Tuscany (from Carlo Collodis text)

Selected Works, Anthologies, and Literary Journal Issues Edited by M. L. Rosenthal

Selected Poems and Three Plays of William Butler Yeats (1966)

The William Carlos Williams Reader (1966)

The New Modern Poetry: British and American Poetry Since World War II (1967)

Chief Modern Poets of Britain and America, Fifth Edition (with Gerald Dewitt Sanders and John Herbert Nelson, 1970)

Ploughshares, Vol. 17, No. 1, Spring 1991. Works-In-Progress Issue

Andrea Carter Brown is the author of three books of poems: Domestic Karma (chapbook, Finishing Line Press, 2018), The Disheveled Bed (CavanKerry Press, 2006), and Brook & Rainbow (chapbook, Sow's Ear Press, 2000). She is co-editor, with Margaret B. Ingraham, of the poetry anthology Entering the Real World: VCCA Poets on Mt. San Angelo (Wavertree Press, 2011). Brown is winner of the Rochelle Rattner Memorial Award, the James Dickey Prize from Five Points and the River Styx International Poetry Prize, as well as residency grants from Yaddo, the MacDowell Colony, and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. She is an editor for the DC-based press The Word Works, and lives in Los Angeles. To read more by this author: Andrea Carter Brown's Intro to DC Places Issue, Summer 2006.

Macha Louis Rosenthal (March 14, 1917 - July 21, 1996), known to friends as "Mac," was born in Washington, DC and taught at New York University. Rosenthal was Director of NYU's Poetics Institute, a Fellow of the American Council of Learned Societies, and a two-time Guggenheim Fellowship winner. He served as poetry editor for three journals: The Nation, The Humanist, and Present Tense. The author of numerous books of poems and poetry criticism, Rosenthal is perhaps best remembered as the editor of several popular poetry anthologies.