In the summer of 1986, while a graduate student working toward my MFA degree in Poetry from the University of Arizona, I was selected as one of a handful of Working Scholars at the Breadloaf Writers’ Conference in Vermont. Founded in 1926, Breadloaf is the granddaddy of all writers’ conferences in the U.S. It was an honor to be chosen. The scholarship gave me free room and board in exchange for a small work commitment: serving food at mealtimes. The group of Working Scholars—we called ourselves Waitrons—roomed together and quickly bonded. (I remain friends with some of those writers to this day.)

Each of us was given the opportunity, in addition to attending readings and craft lectures, to have a manuscript evaluated by one of the featured writers. My first choice was Philip Levine. I was assigned my second choice instead, Donald Justice. That’s certainly an impressive second choice! Who wouldn’t be satisfied with that as a second choice? But while I greatly admired Justice, I loved Levine. Levine’s poems combined a toughness and tenderness that provided me with a model for what the contemporary Jewish narrative could be, and he had a significant impact on my early development as a poet.

In the first few days of the conference, I noticed that Levine was rarely seen at the public events. Other than taking his meals in the dining hall, I most often saw him on the tennis court. He had a loping, sloppy style of play, dashing after the ball with his long spindly arms and legs paddlewheeling. But he was surprisingly good at the game, for all his lack of grace. I didn’t play tennis. I wondered: how could I attract his attention? How could I make this man notice me?

When Levine gave his craft talk, I sat eagerly in the front row. The main point of his talk was the importance of any writer’s ability to absorb failure. He said we would fail constantly, that failure was a crucial part of our growth, and that we should welcome it. Language was too imprecise, connotative meaning too fleeting, denotative meaning even more so. Failure was inevitable.

Levine taught at two universities: Princeton (where he was then a visiting poet) and CalState Fresno (where he was a long-term member of the faculty). At Princeton, he related, his students had never done anything their whole lives without succeeding. It was bad training, he said. When he told them in class that their poems had failed, they wept. (He expressed this with great surprise!) But at Fresno, he said, his students were tough and working class. When he told them their poems had failed, they said, “Fuck you, Levine,” and went home and wrote another poem.

Later that day I walked into the nearby small town, thinking about what Levine had said. Was I tough enough?

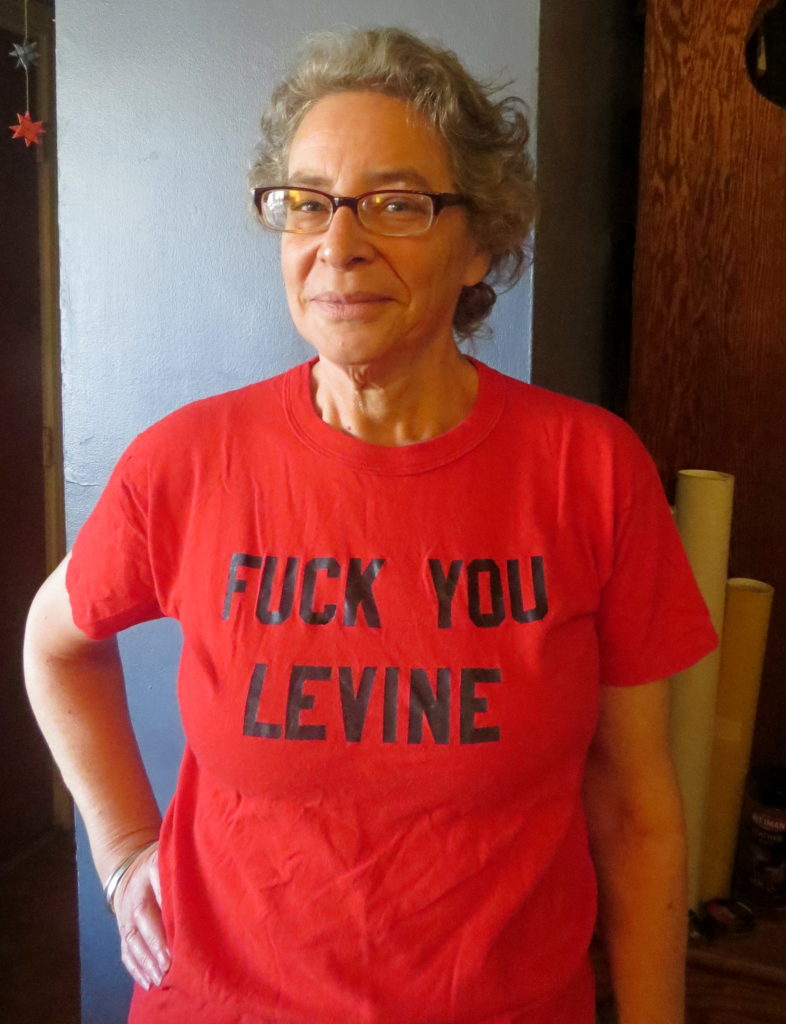

I stopped in front of a gift shop that advertised custom-made T-shirts, and a sudden idea struck me. I went in and bought a half-dozen bright red shirts, with my message printed in bold black letters. And that night, over dinner, I got some of my fellow Waitrons to each wear a shirt under their apron, and we surrounded his table. Levine looked up from his plate as if we’d caught him doing something illicit. I cleared my throat and made a little speech: how moved we were by his talk that day, how humbled we were by his presence among us, how strongly he’d influenced us. Levine looked startled. I said we wanted to give him a tribute in our own small way—and then we each removed our aprons. Our shirts said in capital letters, “FUCK YOU LEVINE.”

I made a rather elaborate show of presenting one additional T-shirt, not to Levine, but to his wife Fran, who was sitting next to him. She never got to wear it though. Levine could not have been more delighted: he immediately plucked the shirt out of her hands and stripped down right there in the dining hall. He proceeded to wear the shirt every single day for the rest of the conference.

And he made a big point about learning each of our names, and coming to our Waitron readings, where he sat in the front row grinning in his bright red T-shirt. At the end of the two weeks, he inscribed my copy of his Collected Poems, “To Kim Roberts, who says Fuck You and makes it sound like song.”

From l. to r.: Tom Aslin, Katherine Miller, Andy Tang, Philip Levine, Kim Roberts, and Richard Chess. Summer 1986.

Kim “I Can’t Believe I Still Have this T-Shirt” Roberts, 2018. Photo by Dan Vera.

Kim Roberts is the editor of the anthology By Broad Potomac’s Shore: Great Poems from the Early Days of our Nation’s Capital (University of Virginia Press, 2020), selected by the East Coast Centers for the Book for the 2021 Route 1 Reads program as the book that “best illuminates important aspects” of the culture of Washington, DC. She is the author of A Literary Guide to Washington, DC: Walking in the Footsteps of American Writers from Francis Scott Key to Zora Neale Hurston (University of Virginia Press, 2018), and five books of poems, most recently The Scientific Method (WordTech Editions, 2017). http://www.kimroberts.org